|

published in

in Times of Israel on November 21, 2024. Despair, unfeasible separation from the Haredim, or an Israel 2.0 roadmap by Dan Ben-David Some are giving up. Others are leaning toward the illusion of dividing

Israel into cantons of different population groups – even though the idea is

unsustainable because it sidesteps the nation’s fundamental domestic issues.

However, there are also the four cornerstones of the Israel 2.0 Roadmap, which

focus on the country’s root problems and could save its future – if we’re able

to harness the public anger against the current default whose existential

implications are becoming clearer day by day. Many

among us have already given up on the possibility that we can truly continue

living together in this country – with the recent Haredi attempts at draft

evasion during wartime only emphasizing the deepness of our domestic chasm.

Outrageous patchwork policies substituting for strategy have been the hallmarks

of one failed government after another. Kicking the can to subsequent

generations has created the trajectory upon which the State of Israel has been

moving along for decades – and at an increasing speed over the past two

years. It’s an unsustainable trajectory

that has led some to give up and leave, or to considering leaving. Their

destination: countries that have recently begun to remind us why our parents

built the Israeli miracle here for us in the first place – reestablishing,

after two thousand years, a collective home that enables us to defend ourselves

in a concentrated and successful manner. Despair

is not an action plan. Others, however,

do have a plan, one that is based on the division of the country into cantons,

as if we were Switzerland: with each canton living as it wishes. The idea may

sound appealing, but as will be shown below, it’s not built upon solid

economic, social, or security foundations that can hold up over the years. As

the storm around us rages, there is no avoiding the fact that a country

desiring life must

candidly face and genuinely confront the root problems jeopardizing its future

existence – and to do so before the demographic window of opportunity closes.

Such a framework marking the way forward is presented here. The

cantonization illusion The

notion of cantons is particularly appealing to those unwilling to genuinely

confront the root problems that have been determining Israel’s direction for

decades. The primary idea underlying this approach is to divide the country

into cantons according to the majority populations in each area, with those

populations determining for themselves: the degree of internal democracy, if

any; lifestyles of work or non-work; schools that provide, or do not provide,

the tools to work in a modern economy, that teach or do not teach the

fundamentals of liberal democracies and respect for others; as well as

determination of taxes and public expenditures. In addition to canton

leadership, there will be a federal, nationwide government with little

influence on what happens within the cantons, with each canton having equal

representation in the national Knesset. There

are different variants of the Israeli canton initiative, but the guiding

principle is that each population group needs to respect the values of the

other groups for the national model to succeed. Also, the strong cantons are to

assist in funding the weaker cantons, with such funding to decrease over time.

This decrease is intended to encourage weaker cantons to understand that if

their model is not economically sustainable, they will need to change it

accordingly. The

first basic problem of Israeli cantonization is security: who will defend all

the cantons from those who want to annihilate the entire country? How is the

canton idea different from current reality in this context? The second basic

problem is economic: those who do not provide a proper education for their

children will not have future adults capable of implementing a turnaround if

and when it becomes clear that aid from the other cantons has ended. The

prevailing illusion that a Haredi education suffices for attaining academic

degrees, even in lieu of a complete and high-quality core curriculum as

children, shatters in the face of reality. According to the State Comptroller,

53% of Haredi women and 76% of Haredi men drop out from the academic track. It

is important to emphasize that these high dropout rates are not from research

universities but from generally low-quality non-research colleges. If a

population unable to sustain itself is reduced to hunger, the pressure on the

other cantons to continue funding it, despite previous agreements, will

increase (sounds familiar?). Otherwise the destitute will be forced against

their will to steal from those who have, in order to subsist and remain alive.

And what about health services among those who do not prepare their children to

follow in the footsteps of Maimonides, who was a physician, and do not have the

ability to fund medical treatment provided in the other cantons? All

this raises the third, and perhaps the primary, problem. What makes people

think that a canton that is not democratic in the way it determines its leaders

– one that is based on discrimination against women and intolerance of all who

are unlike them – will adhere to democratic rules of the game with the other

cantons? To some extent, Jerusalem and other towns that are becoming Haredi

(ultra-Orthodox) serve as an example of the entire country’s direction and the

dangers of the canton idea as a future option for Israel. Jerusalem

and the increasingly Haredi towns: A parable for Israel In a

little over three decades (from 1988 to 2021), the share of pupils in

Jerusalem’s secular primary schools plummeted from 33% to 9%. By 2021, almost

half (46%) of primary school pupils in the city were Haredim, a third were

Arabs, and 11% studied in religious Jewish (non-Haredi) schools (which also

experienced a decline – albeit relatively moderate compared to the secular

schools – in its share of total pupils). As a result of Jerusalem’s rapidly

changing demographics, and their implications for the city’s tax base, the

Israeli government is forced to channel increasing budgets to help keep the

city afloat. For illustration, between 2012 and 2020, the city’s tax revenues

rose by 34% while its income from the Israeli government grew by 138%. In

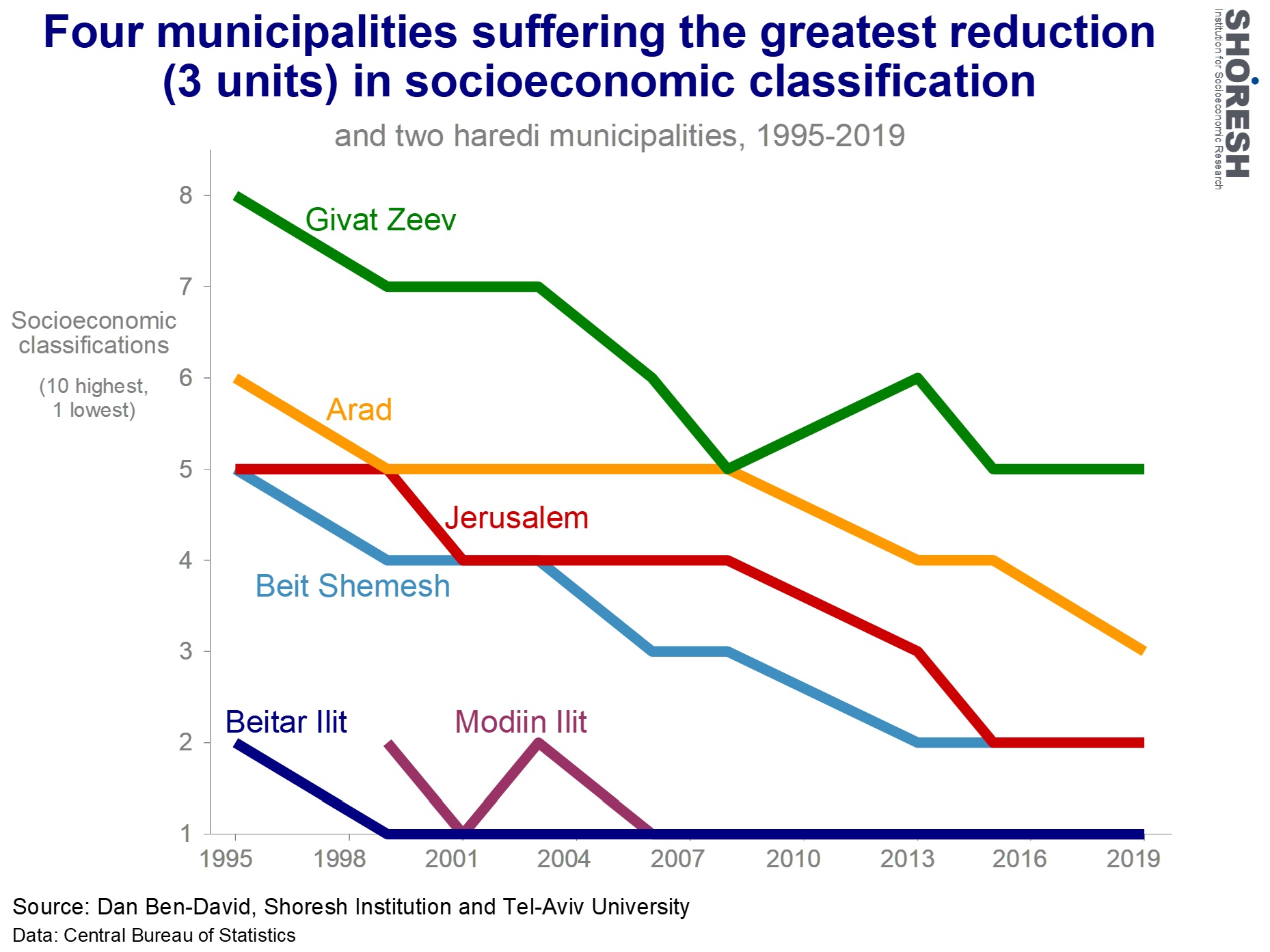

1995, the Central Bureau of Statistics ranked Jerusalem in a medium

socioeconomic cluster (rankings range from the poorest towns in cluster one to

the wealthiest towns in cluster ten). Within just two and a half decades, the

city dropped by three clusters, from cluster five to cluster two by 2019. This

is not a phenomenon that characterized Tel Aviv, which remained in its

relatively high cluster eight level throughout the entire period. Haifa

(cluster seven) and Be’er Sheva (cluster five) also remained in their same

socioeconomic clusters between 1995 and 2019. In

general, Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics classified over 200

municipalities according to their socioeconomic status. Some of these exhibited

improvement over the years while others remained constant or declined.

Jerusalem, along with three other towns, experienced the largest drop in

socioeconomic classification – each of them falling by three clusters.

One

of these towns, Beit Shemesh, was ranked in cluster five in 1995 and dropped to

cluster two by 2019, similar to Jerusalem. Arad dropped from cluster six to

cluster three during the same period, while Giv’at Ze’ev was ranked in cluster

eight (like Haifa) in 1995 and dropped to cluster five over the years. The

Haredi towns of Beitar Ilit and Modiin Ilit are already in cluster 1, the

direction that the other towns are rapidly heading toward. The

particularly high birth rate among the Haredim necessitates finding housing

solutions for the society that is growing faster than any other population

group in Israel. This is due to a fertility rate (6.4 children per woman) that

is significantly higher than that of all other population groups in the

country: 3.8 among religious non-Haredi Jews, 3.0 among Muslims, 2.4 among

traditional Jews, 2.0 among secular Jews, 1.9 among the Druze, and 1.8 among

Christians. As a result, the proportion of Haredim in Israel’s population

doubles every 25 years – that is, in each generation. For example, the Haredim

constitute 6% of those aged 50-54, but are already 26% of their 0-4 year old

grandchildren. Consequently,

the Haredim require more and more areas to live. Alongside towns built

exclusively for the Haredim, like Beitar Ilit and Modi’in Ilit, there is

significant migration of Haredim into towns that were not previously Haredim.

Beit Shemesh, Arad, and Giv’at Ze’ev, who have exhibited the most significant

socioeconomic declines, have also experienced huge and very rapid increases in

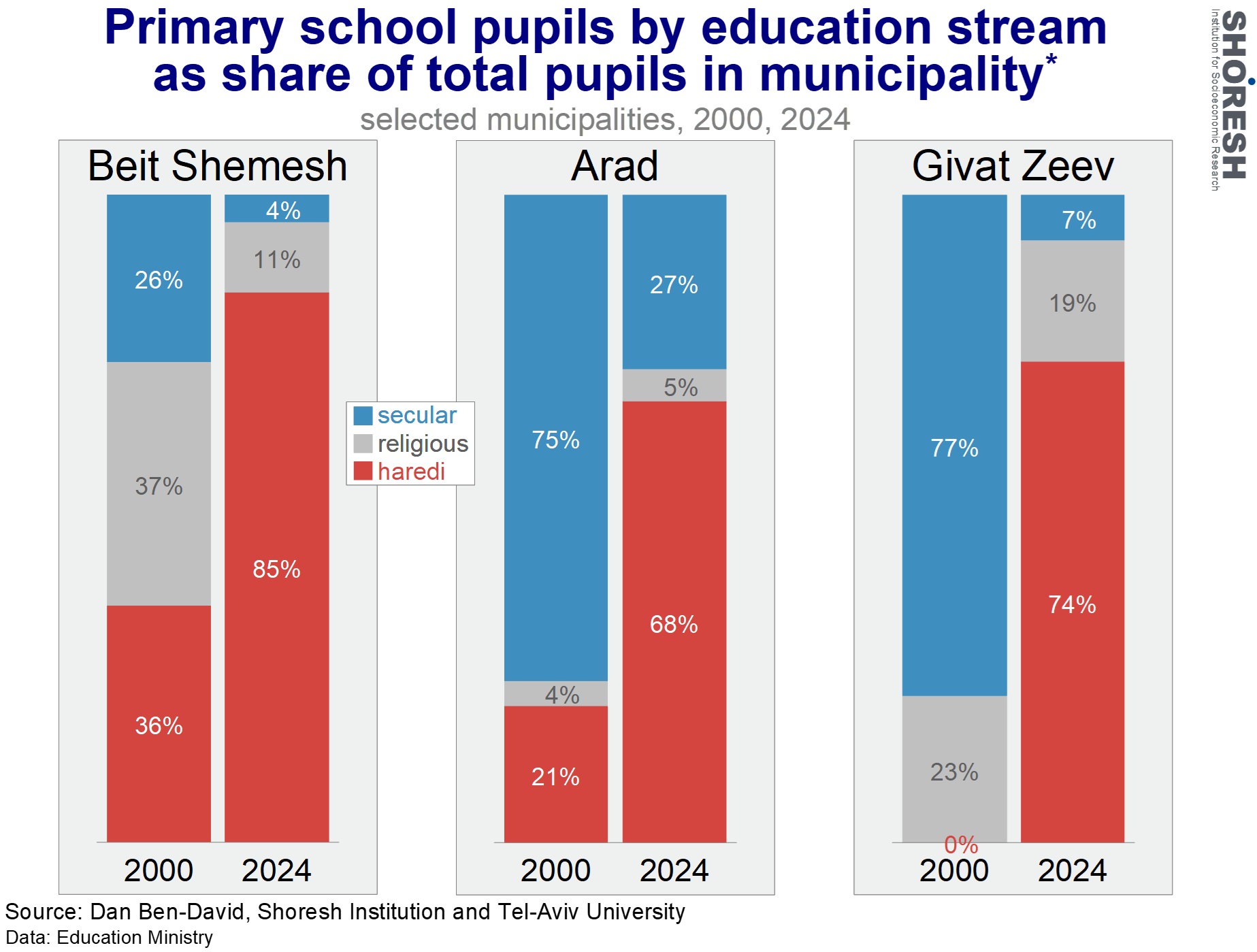

their Haredi populations. As

shown in the second graph, over a third (36%) of Beit Shemesh’s primary school

pupils were enrolled in the Haredi stream in 2000, with a little over a quarter

(26%) in the secular Jewish stream, while the remainder (37%) were in the

religious Jewish (non-Haredi) stream. By 2024, the proportion of Haredi pupils

in Beit Shemesh rose to 85%, and the share of pupils in the secular schools

dropped to just 4%.

In

2000, Arad was a relatively secular town. Three-quarters of its primary school

pupils attended the secular Jewish stream, and only 21% were in the Haredi

stream. Within just 24 years, the demographic distribution was reversed, with

the Haredi stream’s share rising to 68% and the secular stream dropping to just

27%. In Giv’at Ze’ev, there were no Haredi schools at the beginning of the

millennium. In less than two and a half decades, the share of pupils in its

secular schools collapsed from 77% to 7%, while the Haredi share reached 74%. The

remarkably quick tectonic demographic changes in the towns becoming

increasingly Haredi are due not only to inward migration of Haredim because of

their high natural growth. They also stem from the intolerance of the Haredim –

who are not educated otherwise – toward anyone who is not like them. The result

is a free fall in the towns’ more educated secular populations, and

consequently, of those who contribute more economically. This

is the key issue that Israel’s cantonization proponents ignore. As I have

emphasized in the past, one

can be a religious person in a liberal country – but one cannot be a liberal

person in a religious country. Israel’s rapidly changing demographics will

not enable cantons to remain in their original size, while the lack of a

market-compatible and a democratic-compatible education will not enable the

Haredi canton to free itself from dependence on the other cantons for its

economic survival and its physical defense. As such, the cantonization proposal

produces the same existential outcome that Israel is already headed toward. Since

neither Israel’s current trajectory, nor the idea of cantons, is sustainable in

the long term, there is little choice left but to try a third way: the Israel

2.0 roadmap. This roadmap has four cornerstones that address the root problems

and ensure Israel’s future. Israel

2.0 Roadmap Cornerstones

1 and 2 of the roadmap outline significant policy changes that will enable high

living standards in a growing economy alongside low poverty rates – an advanced

economy capable of ensuring Israel’s ability to defend itself in the future.

Cornerstones 3 and 4 are necessary to consolidate cornerstones 1 and 2 so that

Israel remains on the sustainable path. 1.

Overhauling

the education system As I

showed a few months ago, Israel’s

level of education in core subjects is at the bottom of the developed world

(this is not because of the Haredim, most of whose boys do not study the

material and therefore are not tested – which would have lowered the national

average even more). As such, the emphasis should be on overhauling the entire

system and not focusing solely on the Haredim. ·

Israel has

cutting-edge research universities. The knowledge is already here; there is no

need to import it from other countries. We just need to ensure that this

knowledge reaches all the country’s children. High quality universal education

will be a game-changer. The main elements of the upheaval should include: -

A significant

upgrade of the core curriculum across the entire system; -

The core

curriculum must be uniform and compulsory in all schools, including each

religious and haredi school; -

A fundamental

change in how teachers are selected, trained, and compensated; -

A comprehensive

reform of the Ministry of Education and its operations; -

An absolute

prohibition on political parties’ involvement in the content taught in the

education system. ·

Children with a

firm grasp of the basic skills will have opportunities for economic and social

mobility that they might not otherwise have, while contributing to economic

growth at the national level and reducing their personal dependency on others. ·

A common

top-tier basic education will provide a clear understanding of the dos and

don’ts of a liberal society – regardless of personal preferences along the

religious-secular spectrum – teaching the type of critical thinking that will

diminish the appeal of populist and charlatan leaders proposing simplistic and

dangerous solutions to complex existential problems. ·

Better educated

adults will also understand the incumbent requirements and personal

responsibilities of parenthood and will be more judicious in their fertility

decisions. 2.

Overhauling

governmental budgetary priorities ·

including: -

Complete

cessation of funding to schools that do not teach the full core curriculum; -

Discontinuation

of benefits that incentivize non-work lifestyles; -

Full budgetary

transparency so that the public will know what are Israel’s actual national

priorities – and among them, who the government supports and how much they

receive. ·

Money, or the

withholding of it, encourages compliance with the rule of law and spurs

willingness to accept an education overhaul, to work, and to defend the nation. ·

The massive

change required in budgetary priorities should be based on a national agenda

rather than on sectoral and personal ones – a national agenda that will

eliminate the biased and unequal system of benefits, subsidies, discounts and

exemptions. 3.

Electoral

reform ·

The ability to

pass and implement overhauls of the magnitude described above requires a

government comprising cabinet ministers who understand what their ministries do

within an executive branch capable of implementing its decisions and enforcing

laws; ·

Establishment

of effective checks and balances between the three branches of government to

ensure that no lines are crossed. 4.

Drafting

and ratifying a constitution ·

To make it more

difficult for subsequent governments to overturn the systemic overhauls in

education and budgetary priorities, there is a need to draft and ratify a

constitution that entrenches national foundations protecting fundamental rights

and the new system of government. ·

Given the

rapidness of Israel’s demographic changes, this constitution needs to hold for

at least the next two or three decades – until the overhauls in education and

benefits begin to have an effect on future generations, so that there will not

be a future majority in Israel interested in weakening Israel’s democratic

foundations. The

social, economic and political processes that Israel has been undergoing in

recent decades have brought the nation to its moment of truth. While many

Israelis may recognize the symptoms, most do not grasp the full picture

depicted above, nor the fact that this picture is changing at an increasing

pace – with existential implications for Israel’s future. The

Israel 2.0 roadmap bridges liberal right and left, as well as liberal religious

and secular individuals – and they still comprise a majority in the country, if

they just come together as they do in war. After all, the goal is the same,

saving Israel’s future. In the most recent national elections, 1.2 million

voted for the Haredi and Jewish supremacist parties. In contrast, about 3

million voted for non-religious Jewish parties and about half a million for

Arab parties. Among the 3 million who voted for the non-religious Jewish

parties, there are nonetheless many who view as enemies of the state high-tech

workers, physicians, scientists, and fighter pilots opposing Netanyahu and his

partners in pushing for the judicial coup. But they, together with the Haredim

and supremacists, still constitute a minority – though not forever, given

Israel’s demographic direction. This

summer, together with colleagues from the Shoresh Institution, I presented the

cornerstones of the Israel 2.0 roadmap to each of Israel’s opposition leaders,

those leading parties and those intending to establish them (such briefings

were also offered to the Prime Minister, the Finance Minister, and the

Education Minister, but only the latter agreed to meet). Each of the opposition

leaders, from the right to the left of the political spectrum, expressed

agreement with the roadmap. The problem is that the roadmap is so difficult to

implement politically that it requires (a) a coming together of the political

leadership willing to set aside sectoral differences and reaching public

agreement on the roadmap, and (b) the unification of Israel’s liberal majority

around the roadmap’s principles – which requires shifting the public discourse

to the issues described above. This is why I am writing these lines. Everything

begins with replacement of the current captain and his team, who are only

accelerating our advance toward the iceberg ahead of us. It also requires that

we stop arguing about the rearrangement of deck chairs on the Titanic and start

jointly setting an irreversible change of course for the ship. Otherwise, that

iceberg will be the end of us all – or for those seeking temporary lifeboats

abroad, it will be the freezing waters when these boats overturn on them or

their children when they have no mother ship to return to. To

all the leaders of the opposition: this is a time for leaders capable of

putting aside partisan and personal considerations, of coming together to lead

protests like the country has never seen before. Only together can you stop the

poison machine assembled by the prime minister, which is leading to the social,

economic, and diplomatic destruction of Israel. Show that men and women from

the right and left, religious and secular sides of the political map, can unite

as citizens – as they do in the IDF – for the common paramount goal of saving

Israel's future. Give hope! Action

plan It’s

time to think outside the box. Just as

the IDF has recently demonstrated that it is possible to carry out missions

previously considered impossible, Israel’s opposition leaders need to take

action and do something that has never been done in Israel. 1.

Establish, on a

one-time basis, a single joint political confederation of the entire opposition

(a kind of civilian IDF). 2.

This temporary

political party should present a clear, joint political platform based solely

on the four cornerstones of the Israel 2.0 roadmap on which all of the

opposition leaders agree. 3.

Implement the

plan during the new government’s first year in office. 4.

At the end of

the first year, dissolve the Knesset. We’ll then go to elections under the new

system – and finally embark on a new, sustainable, path. Readers,

take the Israel 2.0 roadmap, share it with anyone you can, and press your

leaders of choice to unite and provide a common vision to save Israel’s future

– a vision that distinguishes between the wheat and the chaff, and addresses

the root problems threatening the Israel’s future existence. The time has come

for restoring hope. |