|

published in Hebrew

in Ynet on October 16, 2024. National Derailment and Emigration from Israel by Dan Ben-David A pivot in national priorities during the 1970s gave birth to Israel’s

current reality and is accelerating the exodus from the country. Only when viewed through the lens of history is it possible to grasp and

appreciate the extraordinary Israeli miracle built here by the founding

generation. Despite wars of existence in the early decades, despite the

exponential growth of immigrant populations arriving with only the clothes on

their backs, despite a period of food rationing to ensure that all were fed,

they built not only towns, roads, and businesses. Somehow, they had the

wherewithal to find and allocate resources to build world-class universities. From Israel’s birth in 1948 until 1973, the year of the Yom Kippur War,

Israel’s population grew by 300%, an amazing pace in and of itself. However, the number of senior faculty members

at the universities increased by 3,600%, twelve times the population growth

rate. Within just 25 years, the founding generation brought Israel very close

to the United States in terms of the share of university faculty in the

population. Years later, these universities provided the primary foundation

that enabled Israel’s leap into the high-tech world, which became not only the

economic locomotive for the entire economy, but also the nation’s iron dome

defense. However, times have changed, and national priorities were derailed.

From 1973 to 2016, the population share of the universities’ senior faculty

members dropped by 60% (the addition of the publicly funded non-research

colleges doesn’t change this picture in any major way). That change is on us,

Israel’s subsequent generations. In those early decades, hospitals were built at a pace that managed to

keep up with the phenomenal population growth. The number of hospital beds per

capita remained more or less constant until 1977. Since then, the number of

hospital beds per capita has been in free fall, decreasing by 47% by 2021. The

result: average hospital occupancy rates in Israel from 2017 to 2019 were the

highest in the OECD. While the average rate of people dying from infectious

diseases in the OECD has been declining since 1975, these rates doubled in

Israel from the mid-1990s until about a decade ago. Although Israel’s mortality

rate from infectious diseases has decreased from its high in 2015, it is still

38% higher than that of Turkey, the country in second place among OECD countries.

While approximately 300-350 Israelis are killed each year in road accidents,

the State Comptroller reported roughly 4,000-6,000 deaths each year from

infectious diseases. That is on us. In 1970, road congestion in Israel was almost identical to the average

of Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. Five decades later, in

2020, the number of vehicles per kilometer of road in Israel rose to 3.4 times

those countries’ average – even though the number of vehicles per capita in

Israel is 32% lower than their average. Neglect of infrastructure – that’s on

us. And what about education in Israel? As we’ve shown at the Shoresh

Institution, Israel’s level of knowledge in core subjects – mathematics,

science, and reading (as reflected in the average PISA exams since 2006) – is

at the bottom of the developed world. This is not because of the many Haredi

(ultra-Orthodox) boys who do not study the material and are not tested. Had

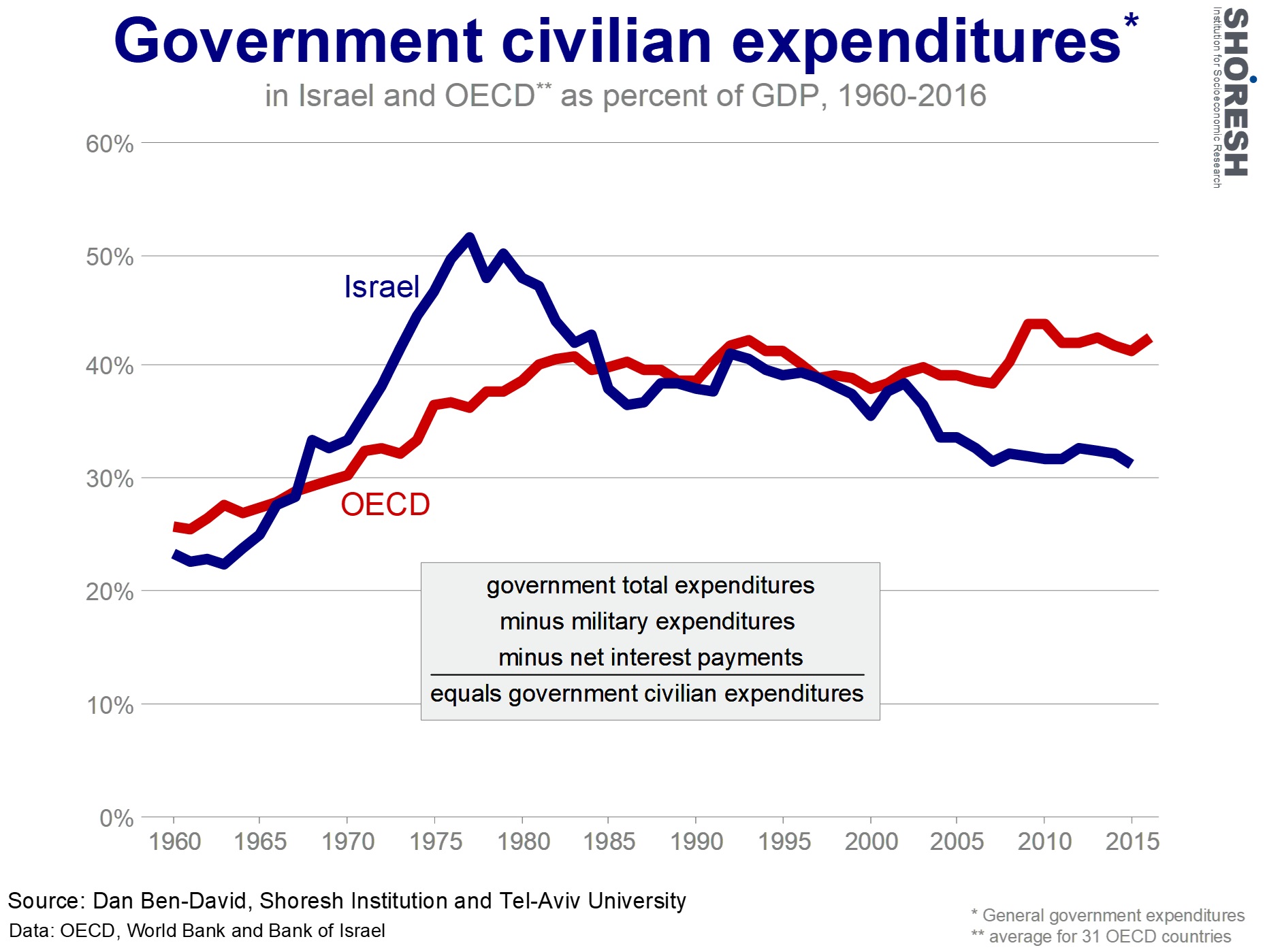

they been tested, Israel’s national average would have been even lower. The common excuse for neglecting Israel’s education, health, and

transportation infrastructures is that defense expenditures were so high that

not enough was left over for Israel’s civilian needs. However, contrary to

popular belief, from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s – the period when Israel’s

internal pivot took place – the nation’s public civilian expenditures (i.e.,

after deducting defense expenditures and interest payments) as a percentage of

GDP were significantly higher than the OECD average (first graph). From the

mid-1980s until the Second Intifada, about two decades ago, civilian

expenditures were very similar to the OECD average.

In other words, for about four decades, Israel spent plenty of public

money on civilian directions. The shift in civilian focus from the mid-1970s

onwards resulted from a change in budgetary priorities, not from a lack of

funds. Lack of budget transparency does not allow us to know how much civilian

money was derailed from national to sectoral and personal directions, but we

all see and feel the results. Even before the last year and a half – the worst since Israel’s birth –

more and more educated Israelis, the backbone of the country’s economy and

society, are giving up and leaving. Looking at all those who obtained an

academic degree in Israel from 1980 to 2010, 2.8 such academics left for every

academic who returned to the country in 2014. Although the absolute number of

those leaving is not high, the ratio of four emigrants per returning academic

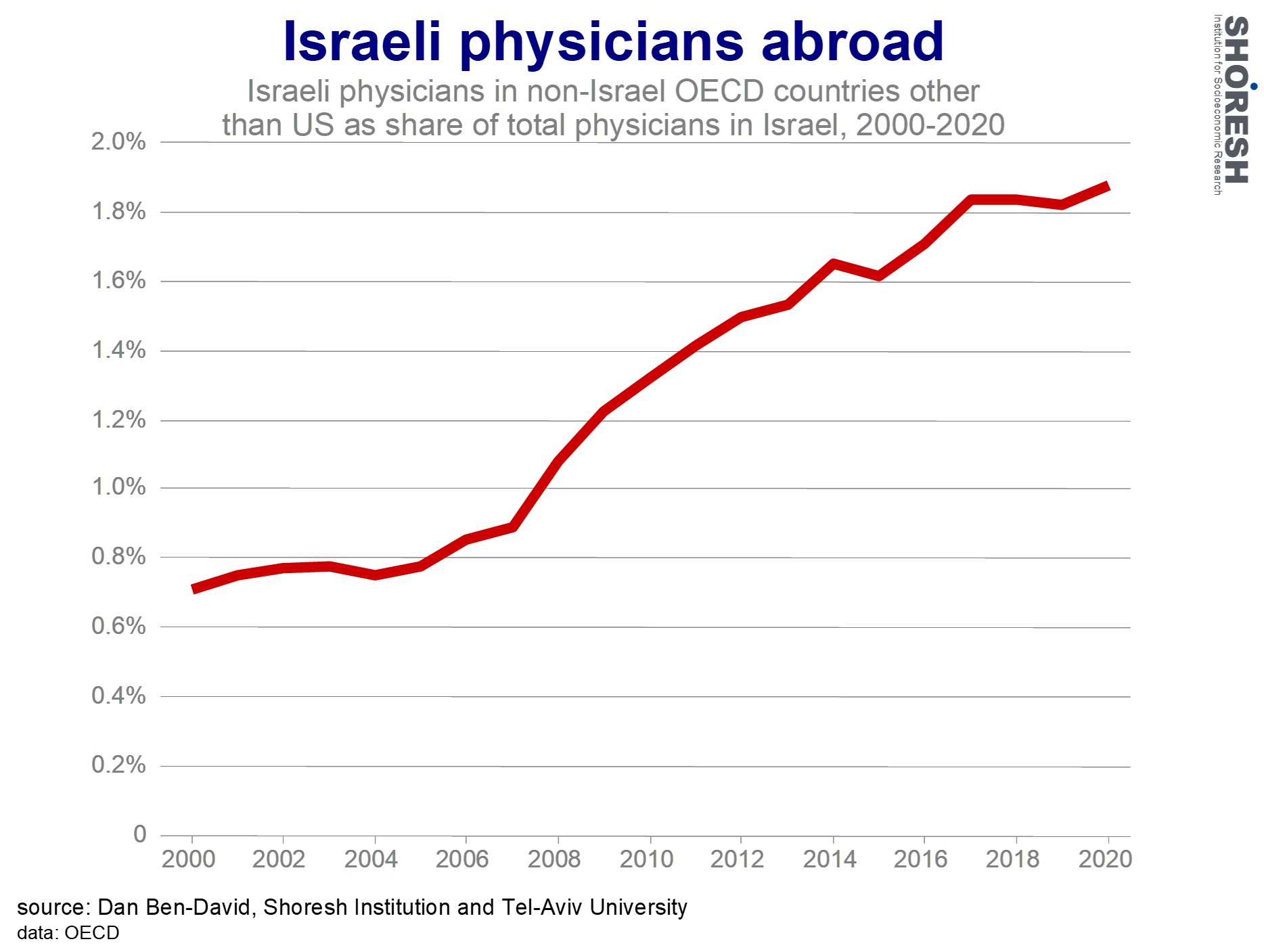

was surpassed within just four years. According to OECD data, the number of Israeli physicians in other OECD

countries, as a percentage of all physicians in Israel, has been steadily

increasing. It has more than doubled during the first two decades of this

century (second graph). These rates are low (although they do not include

physicians leaving for the U.S., which raises the curve even higher), but their

trend is clear.

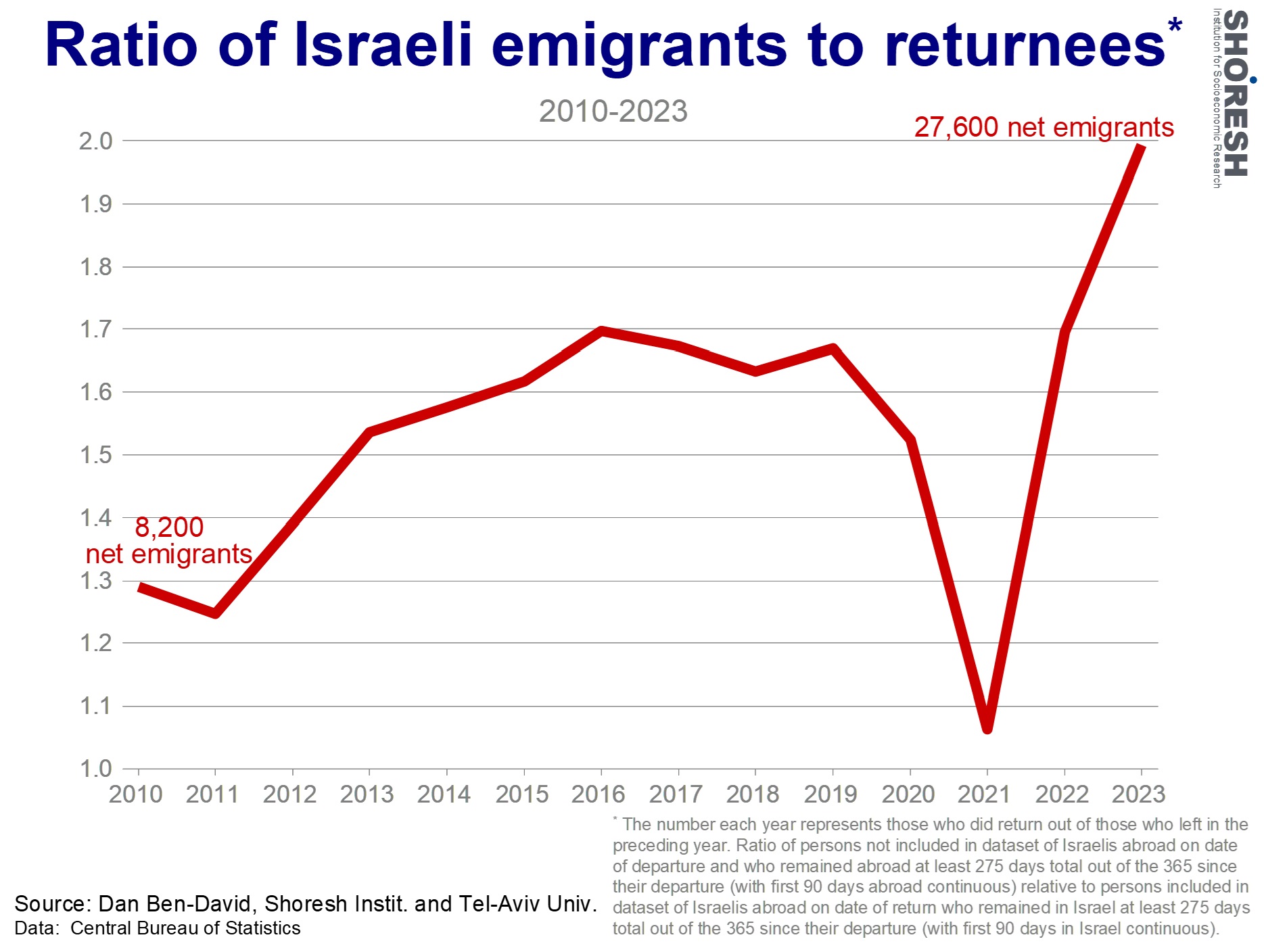

Immigration data recently published by the Central Bureau of Statistics

reflects an improvement in the way that Israel measures migration to and from

the country. Due to remaining methodological issues, annual migration data are

less relevant than the trend (third graph). When expanding the scope from

academics to the general public, the number of Israelis who left, for every

Israeli who returned, grew from 1.3 to 2.0 in less than a decade and a half.

It’s still not possible to get a full picture regarding the departures in 2023

and 2024, but the initial signs are quite problematic.

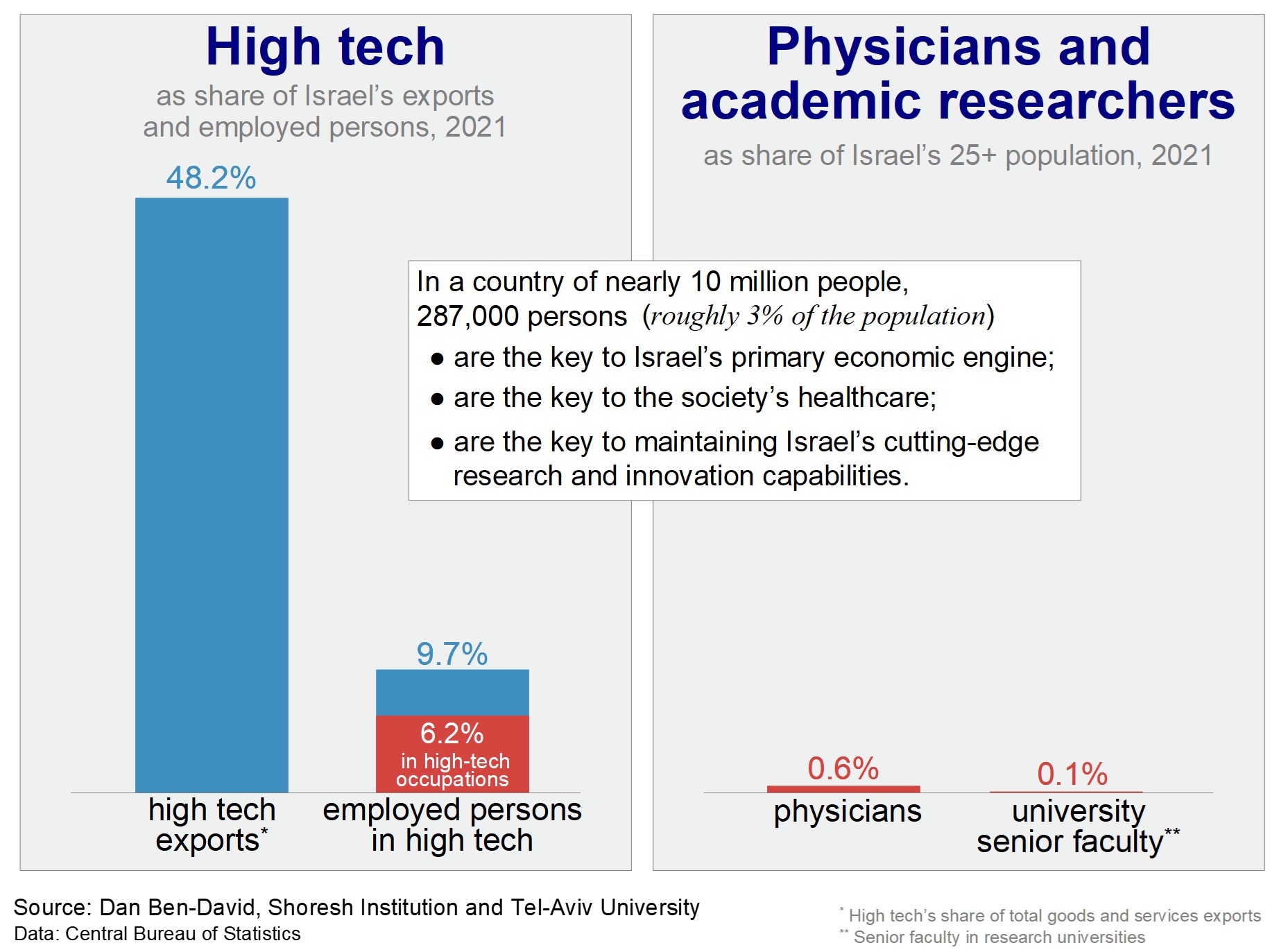

The danger of emigration is highlighted in the fourth graph. The

high-tech sector alone is responsible for about half of Israel’s total exports.

Only a tenth of Israel’s employed persons work in this sector. In fact, only 6%

of Israel’s employed persons are in high-tech professions in the high-tech

sector. The level of medical care we receive depends on our skilled physicians,

who constitute only 0.6% of the adult population aged 25 and over. The senior

faculty at Israel’s research universities – constituting only 0.1% of the adult

population aged 25 and over – are the ones who train the physicians, engineers,

scientists, and computer scientists, all those people who keep Israel at the

forefront of human knowledge.

Altogether, these three groups comprise less than 300,000 people. That’s

it. Israel has a population approaching 10 million. But for the country to fall

below the developed world, we don’t need a million or two to leave. A few tens

of thousands from this group are enough, and Israel will begin a spiral of

collapse of the kind that 130 of the country’s leading economists warned about

in May of this year. After decades of gradually increasing emigration in small doses, the

past year and a half has caused many to internalize where all the long-term

processes described above have been leading Israel: the attempted judicial coup

from early 2023 and the continuing efforts to achieve it today; the October

horrors and incomprehensible savagery when parts of the country were occupied;

a divisive governing culture that turned the skilled and educated, the pilots,

and families of hostages into enemies of the state; increasing destruction of

Israel’s diplomatic relations with other countries; an escalating war with a

government whose intent to hold onto power far exceeds its concern for the

overall good of the nation; and the insistance of the Haredim – whose share in

the population doubles every 25 years – on evading the defense and economic

burdens. Over all these flies the largest black flag in Israel’s history. In conclusion, a few select sentences from the warning letter signed by

the 130 economists, including myself, at the end of May: “Without a change in the current trajectory, these processes endanger

the country’s very existence. Many of those who bear the burden will prefer to

emigrate from Israel. The first to leave will be those with opportunities

abroad … Israel’s remaining population will be less educated and less

productive, thus increasing the burden on the remaining productive population.

This, in turn, will encourage further emigration from Israel. This process of a

‘spiral of collapse’ in which increasingly larger groups decide to emigrate,

will further deteriorate the conditions of those who remain, while severely

impacting populations with fewer emigration options, including the Haredi

population itself. The demographic and economic processes that the city of

Jerusalem has undergone in recent decades – its rapid decline in socioeconomic

indicators and its increasing abandonment by large segments of its secular

population – clearly illustrate this spiral of collapse phenomenon and the

dangers facing the entire State of Israel. Jerusalem has Israel to support it.

But Israel has only itself.” “This is a clear and present danger to the country, one that we assess

has a very high probability of realization … The danger is clear, and in our

estimation, the probability of its realization is very high... This is a real

alarm. History will not forgive the State’s leaders in the present and future –

from all ends of the political spectrum – if they stand by.” The coming months and years will require enormous outlays on

rehabilitating and compensating the scores of physically and mentally wounded

as well as those harmed economically, rebuilding and strengthening Israel’s

defense systems and the areas in the northern and southern parts of the country

that have been damaged and evacuated.

The magnitude of the resources required for the rebuilding of Israel

will not leave any degrees of freedom for the continued funding of narrow

sectoral demands. If there was ever a

time for Israel to reset its national priorities, it will be the Israel 2.0

that we will need to rebuild. |