|

published

in Times of Israel

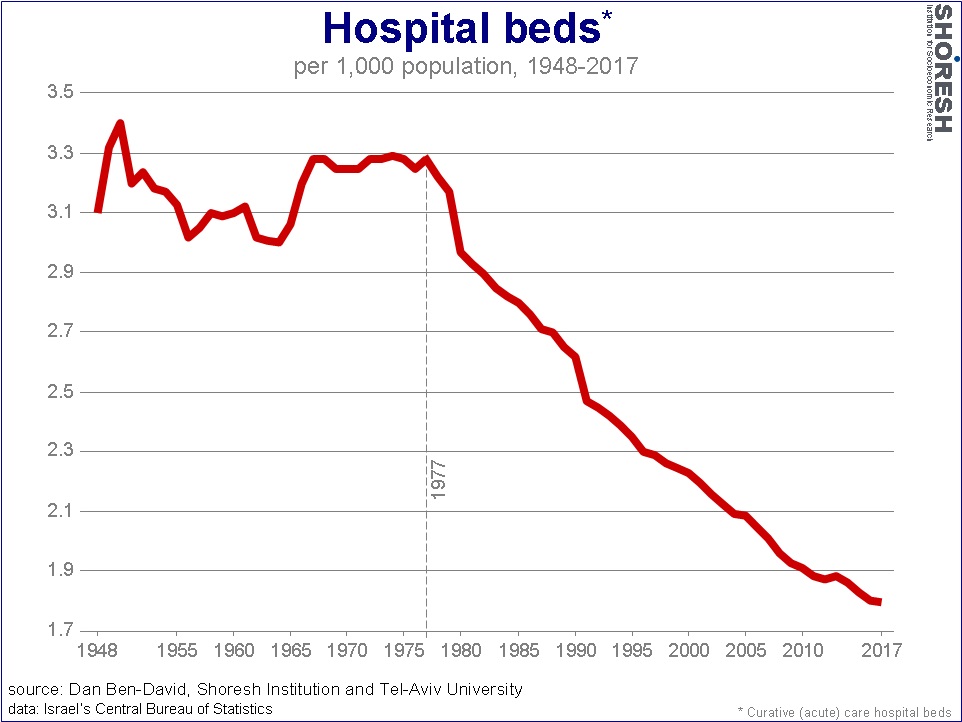

on March 12, 2023. Part 2 of 5 Israel’s priorities pivoted in the 1970s. Israelis today are

paying the price by Dan Ben-David Traffic jams and packed hospitals are just two results of decades

placing sectoral interests above national ones The enormous national shock caused by the Yom Kippur War, followed by

the country’s political upheaval – from left to right – in the 1970s, led to a

major pivot in Israel’s national priorities, with far-reaching consequences

felt to this day. A small sample of

these changes illustrates just how wide-ranging and deep the effects of this

pivot Israel are. While an ingathering of Holocaust survivors and Jewish outcasts from

Middle Eastern countries, arrived in Israel with only the clothes on their

backs, the country managed to build towns, roads – and, incredibly enough,

research universities that became among the world’s best. Israel’s population grew exponentially during

its first decades, and the number of senior academic faculty rose even faster. By the mid-1970s, the number of senior

faculty per capita in the universities approached American levels.

Since then, Israel’s GDP per capita has risen to more than twice its

mid-1970s level, while the population has grown nearly threefold. The need for top-notch academic institutions

is there, and the means have certainly been available. But Israel’s national priorities have since

been diverted elsewhere, and the number of senior faculty has dropped like a

rock, to less than half of its mid-1970s level. Healthcare suffered a similar fate.

During its very difficult early decades, Israel nevertheless managed to

build hospitals and add hospital beds at a pace matching its exponentially

increasing population. All of that

stopped abruptly in 1977, with the number of beds per capita beginning a

freefall that has continued ever since.

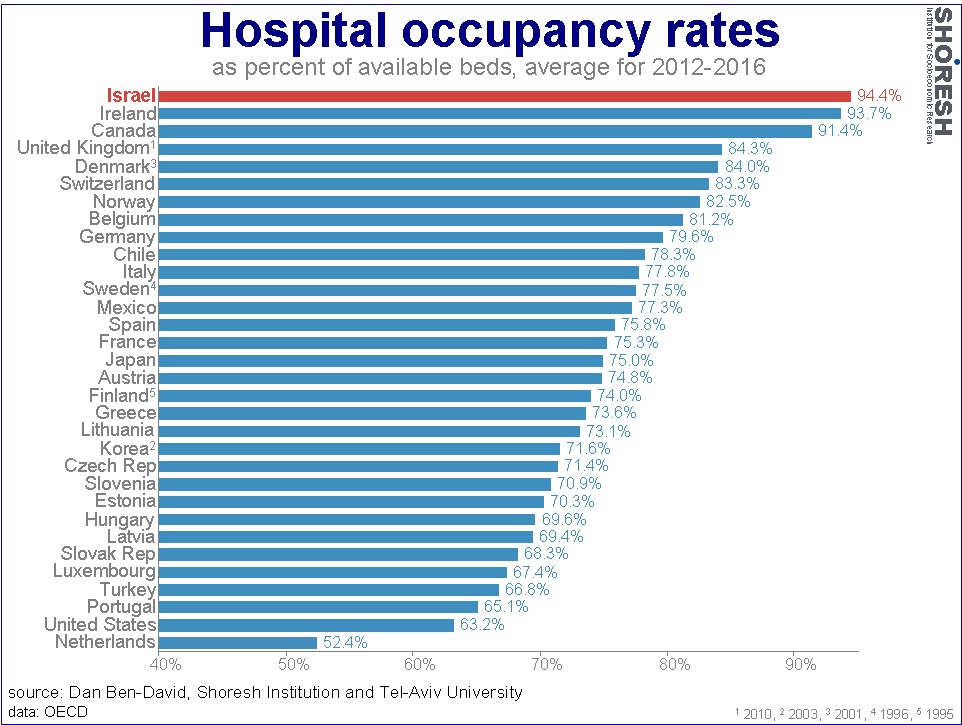

The result has been hospital occupancy rates that were the highest in

the developed world in the period prior to the Covid pandemic. Many of Israel’s hospitals have over 100%

occupancy rates for much of the year, having to place patients in hospital

corridors and dining areas.

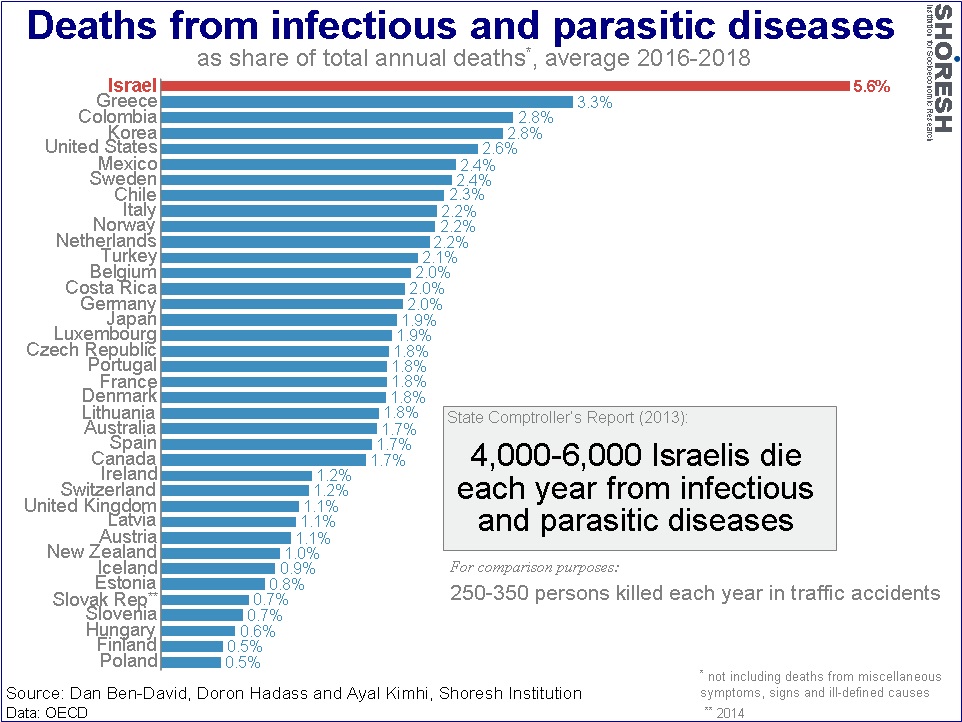

The combination of insufficient staffing – from physicians to nurses to

hospital orderlies – and patient congestion does not provide the safest, or the

most sterile, form of hospitalization.

As a result, the share of Israelis dying from infectious diseases has

more than doubled in just two decades, making Israel a major outlier in the

developed world which experienced nothing like that spike during the same

period.

According to the State Comptroller’s Office, between 4,000 and 6,000

Israelis die each year from infectious diseases, a number that is roughly 17

times the number of persons killed annually in traffic accidents. When compared with the other OECD countries,

the share of Israelis dying from infectious diseases out of all deaths in the

country is 70% greater than the share in the number two country, Greece.

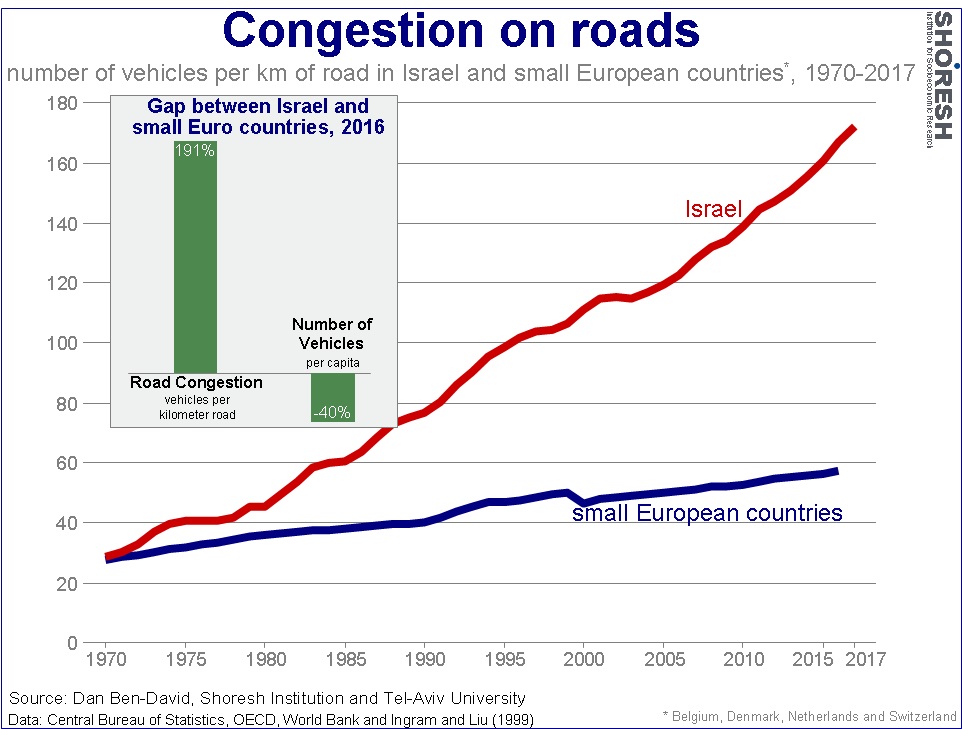

Congestion on the roads plays a major role in reducing

productivity. For example, if a firm

needs to hire twice the number of drivers to deliver the same amount of stock

because they are sitting in traffic jams all day, then the labor productivity

of these drivers is cut in half, with all of the attendant effects that this

has on the drivers’ wages. Interestingly, in 1970, Israel had already managed to reach complete

equality with the small country average in Europe in terms of the number of

vehicles per kilometer of road. Since

then, the congestion on Israel’s roads has risen to nearly three times the

small country average in Europe. This,

despite the fact that Israelis have 40% fewer vehicles per capita.

The reason why Israel’s roads are so congested, notwithstanding the

relative paucity of vehicles, is because of a major underinvestment in the

country’s transportation infrastructure – and in particular, a severe lack of

public transportation alternatives.

Thus, while there is finally a surge in such investment, it is way too

late and not nearly enough to even slow down the significant growth in traffic

congestion. The above are but a few examples of the major diversion of national

priorities away from vital infrastructures.

One could counter – as Israeli governments are wont to do – that it is

not a question of national priorities but rather an outcome of the excessive

defense expenditures that Israel is forced to make because of the inhospitable

neighborhood that it is in. The claim is

that there is simply not enough left in the public coffers to fund non-military

needs. While Israel’s military expenditures are indeed exceptionally high in

comparison with other developed countries, the contention that this does not

leave enough for civilian uses is misleading – at best. The share of government civilian expenditure

(that is, total government expenditures minus defense spending) out of GDP is

indeed below the OECD average in recent years.

However, this was not the case between the mid-1960s until just after

the turn of the century – the decades that were witness to the widescale pivot

in Israel’s national priorities. In

fact, for most of this period, the Israeli government’s civilian expenditures

were not just above the OECD average, they were far above it.

Until recently, money was never scarce and could not have been the

reason for the lack of emphasis on what prior generations deemed important. Since the mid-1970s, the money was simply

diverted elsewhere. While Israel’s national budget is seemingly transparent, with thousand

of budget items listed under the various cabinet ministries, the information

provided to the public is to a large extent meaningless. For example, one might presume that the

Education Ministry budget reflects total government expenditures on

education. However, not all of that

money goes for educational purposes. In

addition, a plethora of other ministries also give money directly, or

indirectly via NGOs that they support, to various aspects – often politically

connected – of the country’s education system. Hence, while it is clear which infrastructures were neglected, it is not

possible to get an accurate picture of where the public resources actually

went. But it is possible to piece

together available information to try and gain a better perspective of what

transpired. After discounting inflation and population growth, there was extensive

growth in government expenditures between the 1967 Six Day War and the 1973 Yom

Kippur War – with the increase in expenditures per capita far exceeding the

growth in GDP per capita. This period

not only covered the War of Attrition with Egypt, but also a major building-up

of the territories occupied in the Six Day War.

While some of this was military expenditure, the spike in civilian

government expenditures is also suggestive in this regard. The government continued to fund the previous

national priorities while beginning to fund new ones emanating from Israel’s

expansion.

The Yom Kippur War was followed by a much stronger jump in total

government expenditures than in the civilian government expenditures, though

the latter also rose steadily over the next decade. With total government expenditures going

through the roof, coupled with an inability to raise taxes to the levels needed

to pay for the expenditures, the Bank of Israel printed money – lots of it – to

cover the deficits. The result was

hyperinflation. Presumably, the post-1973 years were a period of realization that the

government could no longer fund both the pre-1973 national priorities together

with the post-1967 priorities.

Furthermore, the unprecedented addition of the haredim (ultra-Orthodox

Jews) into the governing coalition in 1977, for the first time in history,

meant that even more money had to be channeled in their direction – lots of

money if the subsequent jump in their fertility rates, which coincided with a

freefall in the employment rates of male haredim, is any indication. The bottom line is that with inflation raging and spiraling ever upward

and the need to regain control of the government budget, a decision was

apparently made to replace the old national priorities with the ones reflecting

the new government coalitions. Israel

has been paying the price of this decision ever since. |