Haaretz, February 4, 2005.

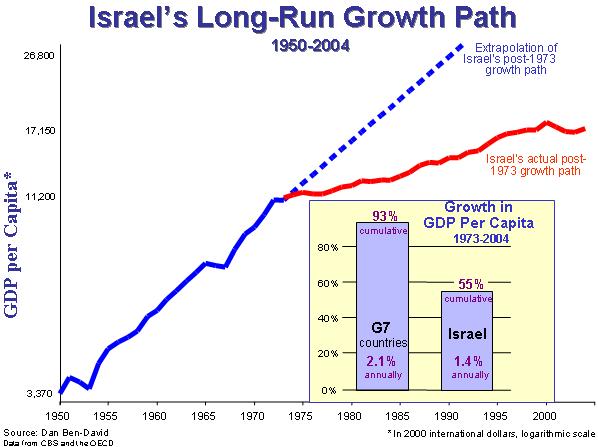

Dan Ben-David Tel-Aviv University After three straight years in which Israeli income levels fell continuously, came 2004, with an increase of 2.4% in per capita GPD, the measure commonly used to indicate standards of living. This is a significant accomplishment that should not be taken lightly. While average United States incomes rose by 16% from 1996 until 2003, average Israeli incomes in 2003 returned to their 1996 level. Thus, it is good news when Israeli incomes have risen above where they were situated eight years ago. As the Israeli economy is apparently beginning to come out of the deep recession and returns to its normal growth path, the good news comes into a more accurate perspective, and the serious economic threat that we are facing begins to materialize. Since the seventies, the country is situated on a number of unsustainable long-run trajectories - low growth combined with high and steadily increasing rates of unemployment, poverty and income inequality - that put its future in jeopardy. Israel veered toward a different socio-economic path in 1973. In the aftermath of the Yom Kippur war, which was the catalyst for what subsequently ensued, the country underwent a seismic transformation of its national agenda. A banana culture of governance took root, mediocrity and superficiality ascended to the top of the pecking order, budget priorities were significantly altered to reflect narrow, personal and messianic interests rather than to promote national interests - and the results are clearly evident in the graph.  The Israeli economy shifted in the seventies from one of the fastest growing in the west to one of the slowest. The country, which had been rapidly catching up with the world leaders has, since the seventies, been steadily falling farther and farther behind. While the average incomes in the leading western countries, the G7, have almost doubled since 1973, Israeli incomes rose by only 55%. Despite everything that Israel has undergone since the seventies - wars, 3-digit inflation rates that the western world hasn't witnessed since WWII, and immigration that increased the country's population by a fifth within half a decade - these events were reflected only in fluctuations around the trend, while the long-run growth path itself appears to some as though it is etched in stone. There can be no greater misconception than this. The factors influencing the slope of a country's growth path are not preordained destiny but the result of its own national priorities. A century has passed since Herzl died, but he already understood then what many of Israel's policy-makers still have not begun to comprehend. "It must be the country of choice" he said, as quoted in Nahum Gross's book. This does not just refer to Jews abroad who have options, but also to a growing number of Israelis who are able to choose where they prefer to live. The steady three decade decline of Israel - in relation to the leading western alternatives - represents an existential threat to the country. In 1999, even before the onset of the severe recession that we are currently emerging from, I wrote in Haaretz (July 13 1999) about the deepening growth crisis and the form that the new national agenda will need to take in order for us to change the multi-decade trajectories. A year later, I repeated these proposals - together with fellow members in a team of leading Israeli academics headed by Haim Ben-Shahar - at a special cabinet meeting convened by Prime Minister Barak, and since then I have also shown them (in differing levels of detail) to Prime Minister Sharon, cabinet ministers, MKs, directors-general of cabinet ministries, and many other policy-makers. Despite all this, it has become quite clear that our national agenda will not change until the Israeli public internalizes the critical implications of our current state of affairs - and begins to demand accountability from its elected officials. Hence, I will try to outline in upcoming articles the socio-economic picture of Israel and detail some of the main features of a new national agenda that has been formulated over the past few years together with colleagues from academia and other professions. There is an alternative to what you see in the graph.

|