The Worst Threat of All

by Dan Ben-David Many illusions were shattered during

the decade ending next week. It was a

decade that began with Camp David and ran head on into a murderous intifada; a

decade beginning with a soaring high-tech that crash-landed within a year; a

decade that America began as the world’s only superpower, and within less than

two years had national symbols crash into the soil of reality; a decade in

which a small country discovered how limited its ability is to defend its towns

from threats from the skies and its soldiers from threats from below the

surface; a decade in which the superpower discovered its limited ability to

deal with small threats with an extremely dangerous potential. In many respects, this decade of

illusions was too similar to 1930s. In

the national security realm, the countdown began for the great cataclysm of the

forties. Are the signs accumulating in

the area of national security this decade pointing to an outcome with similarly

catastrophic potential? In the socioeconomic realm, memories

from the 1930s received a place of honor during the past year – and not by

coincidence. During the first twelve

months of the Great Depression, global output fell by around 13 percent, a

figure echoed in the first twelve months of this current crisis. Eventually, as Eichengreen and O’Rourke so

vividly show in their recent study, output continued to fall during the

Depression and after three years, there was an overall decline nearing 40

percent in global industrial output. The stock market crash during the

Great Depression reached 20 percent at the end of the first year. This time, the collapse during the first

twelve months was much greater, approximately forty percent. In recent months, there have been signs that this

freefall has stopped and there have even been some relative increases. That said, the overall decline in today’s

global stock markets is identical to what it was then at this stage of the

Great Depression. It is important to

point out that that crisis evolved in a series of waves, and within three years,

the average value of stocks world-wide was 70 percent below its value at the

beginning of the Depression. One of the greatest policy lessons

from the Great Depression was in the area of international trade. Countries that saw a steep rise in

unemployment adopted autarkic policies of closing their borders to imports, with

the intention of protecting their workers – which only magnified the

Depression’s blow on other countries. The

result were trade wars that substantially reduced world trade and only worsened

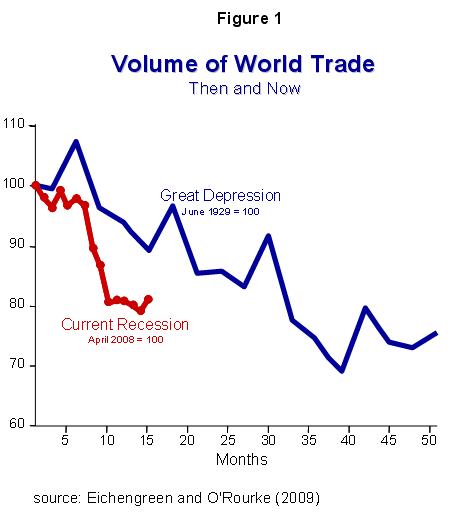

an already bad situation. As figure 1

indicates, during the first three years of the Depression, world trade fell by

about 30 percent.

This time, western economies have been

working together to minimize the recession’s damage – with coordination and

cooperation between governments and consultations between Central Banks. Despite this, the decline in trade this past

year was even sharper than it was during the Great Depression. During the Depression’s first year, global

trade fell by less than nine percent – while during the first year of the

current crisis there was a decline of fifteen percent. During the first half of 2009, the decline

halted, and it is possible that we are changing direction. Israel’s export statistics this past month

point to a sharp positive turn-around. We

may be at the beginning of a possible emergence from this severe crisis. Hopefully, we will then finally open our eyes

and stop looking at the past month, the past quarter, or even the past year –

and start seeing the big picture that reveals a surprising perspective of the

speed at which Israel is speeding towards its future. That future is sitting today on

classroom chairs. Who is sitting there? What kind of a toolbox is it receiving? There is a crucial need internalize how

quickly changes took place during just one decade and understand the

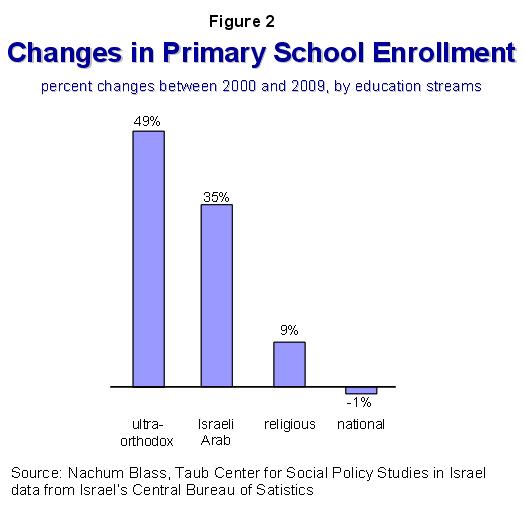

implications. Israel's education system has four

streams: state, state-religious ultra-orthodox and Israeli Arab education

streams. As indicated in figure 2, at

the end of the decade now ending, there are less primary school pupils in the

national education stream than there were when this decade began. In contrast, the national-religious primary

schools have seen a nine percent increase since 2000. The number of primary school pupils in the

Israeli-Arab stream grew by 35 percent, while the number of ultra-orthodox

pupils grew by 49 percent. All of this

transpired in just one decade. About

half of all the primary school children in Israel already study in either the

Israeli Arab stream or the ultra-orthodox stream.

This would be a good time to take

notice of what Israel’s next generation is studying. is it receiving the tools so necessary for

coping successfully in a modern and competitive market? If these children adopt their parents

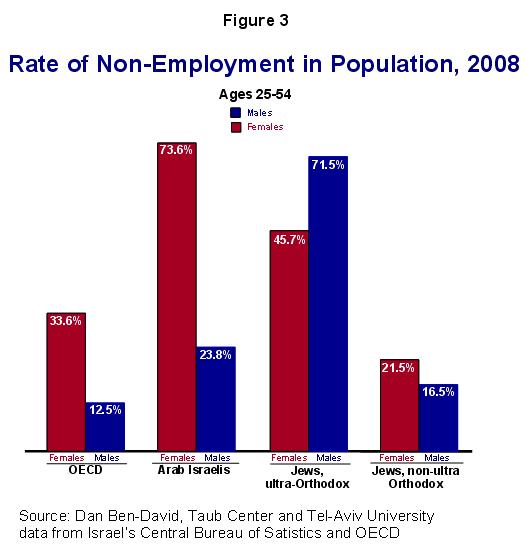

work norms, then what can Israel look forward to in a number of years? Last year, the share of non-employed primary

working age (25 to 54) men in western countries belonging to the OECD was 12.5

percent (figure 3). The percentage of

non-employed Israeli Arab men was almost twice as high. Out of the ultra-orthodox males that are of

primary working age, over 70 percent were not employed. Among females, 74 percent of the Israeli Arab

women and 46 percent of the ultra-orthodox women were not employed, compared to

only a third in the west.

Could such rates of non-employment be

characteristic of the majority in a first-world country? Could a non-first world country survive in

this Middle-Eastern neighborhood? And what about the current majority, that

is destined to become the minority? Non-employment

rates of 16.5 percent among prime working age non-ultra orthodox Jewish males

may look good when compared to other groups, but they are nonetheless a third

greater than is common in the west. How

could this happen? One

explanation is the education that Israel’s children receive in the basic

subjects. Recent studies focusing on

the quality of education the importance of education in core subjects affects

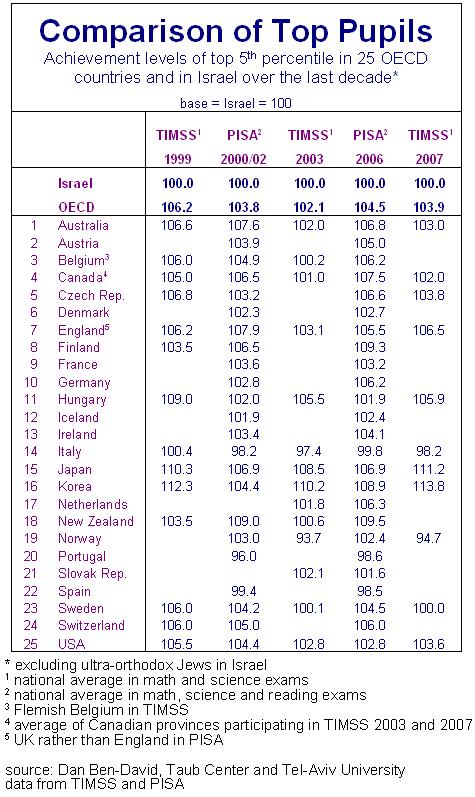

on an individual’s income and the country’s standard of living. A new study by the Taub Center for Social

Policy Studies in Israel, which will come out in the upcoming report on the

country’s society and economy, summarizes an entire decade of international

exams that Israel participated in, comparing the country to a fixed list of 25

OECD countries in each of the years. Since 1999, Israel has participated in

five different international exams in mathematics, science and reading. In all but one of the exams over the past

decade, the achievements of Israel’s children were below every single western

country. In light of the fact that since

the 1970s, Israel’s living standards are steadily falling farther and farther

behind the leading western countries, these outcomes are not indicative of a

change in direction in the offing. Educational gaps within Israel over

the past decade were higher than the gaps within each of the 25 OECD countries

in each of the years. Since economic

gaps in Israel are already among the highest in the west, and in view of the

fact that the education system is the primary jump board to the labor market, then

how could one expect any future improvements when education gaps among seven

million Israelis are greater even than the huge education gaps between 300

million Americans? Since 1999, the educational

achievements of Israel’s weakest students, those in the bottom fifth

percentiles, are lower than the weakest students in every one of the 25 OECD

countries in every one of the exams. This

is a country with one of the western world’s highest poverty rates – and in its

children, one can see what the future holds in store. It is important to point out that pupils in

ultra-orthodox schools, who do not study math or science at core curriculum

levels, do not participate in the international exams. In other words, the children of Israel

managed to garner these problematic achievements without any assistance from

the ultra-orthodox kids. During the decade since 1999, Israel

passed a milestone when its future formally parted ways with its past. The generation that once sat on Israeli

classroom chairs received more Nobel Prizes in the Sciences per capita than any

other country in the world this past decade.

During this same decade, the achievements of Israel’s top pupils, those

in the top 5 percentiles, placed them close to the bottom of the western world

in every single exam (see table). How

ironic it is that while we receive such a reminder of the potential that Israel

society has – we also witness the terrible bungling of the baton’s passing from

our generation to our children’s.

It is possible to see the picture that

developed here during the decade ending next week and return our heads to the

sand. We can look for false comfort in

the delusion that this is destiny. We

can continue to depend on politicians who act as though there is nothing that

can be done. We can ignore, and we can

pack suitcases. But

there are also other possibilities. We

can stop incessant bickering on side-issues, and start distinguishing between

what is truly important and what is not.

Dreams can not be a substitute for an operational plan – and there is

such a plan. The kind of systemic

reforms required in education, employment and in other areas do not have a

chance of passing in the current electoral system in which personal and

sectoral incentives far outweigh national concerns. When instability is inherent in the

system, when the executive branch comprises heads of competing political parties

who view policy as a zero-sum game – where your failure is my success – when a

third of the legislative branch is in the executive branch while the other two-thirds

do all the can to bring down the first third, when all of the fragments of

parties representing the heart of Israeli consensus barely constitute a

majority in the Knesset, there is no other issue more important for saving the

country’s future than a comprehensive change in Israel’s system of government. I happen to favor a particular system

that I have often written about in the past – with a president as chief

executive and MKs all having to get elected on a personal basis to fixed terms

of office, with a complete separation of powers between branches that includes

checks and balances which will enable governance on the one hand and oversight

on the other, with cabinet ministers who are chosen to their positions not

because they head political parties but because they are people who actually

know something about the offices that they head – but this is not the point. There is no perfect system, and there are

other possibilities, The point is that

we may not have another opportunity to learn from our mistakes. This is a time for real leaders, and

there are some in the Knesset, who understand the importance of the hour and

what will be their place in the history of the Jewish people if they don’t

start taking care of its home. Each one

cannot do it on his or her own. But

together, they can. This is one of our

best and last opportunities. The decade

that begins next week must be our reality check decade, otherwise it could be

the countdown decade.

|