|

PDF file

published

in Haaretz on April 13, 2008.

The Third Tuition Option

by Dan Ben-David Should we raise or lower tuition in

the Israel’s public universities? The

fact that there are valid arguments made at both ends of the polarized spectrum

has not proven very conducive for solving one of the most serious problems

currently deeping the country’s academic crisis. But there is a third tuition option for

solving this issue, an option that connects between the compelling facts

underlying the two opposing positions and brings them together with additional

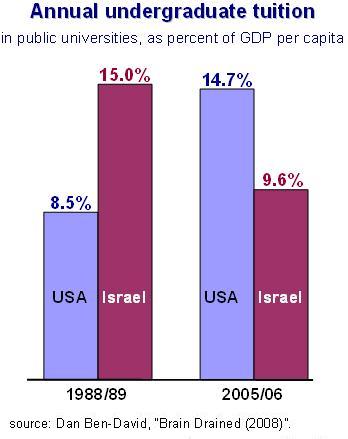

elements barely visible on today’s public radar. Twenty years ago, undergraduate

tuition at public American universities was 8.5 percent of U.S. GDP per capita (the

common measure for living standards). In

Israel, undergraduate tuition reached 15 percent of the country’s GDP per

capita. Since then, the two countries

switched places. In the 2005/2006

academic year, the ratio of tuition to GDP per capita rose to 14.7 percent in

the States and it fell to 9.6 percent in Israel. When this is the only vantage point

that one takes on this issue, it is not hard to understand the insistence by

some that Israeli tuition fees be raised.

In addition, the probability that a university graduate will find

employment is higher than that of a high school graduate, while the salaries of

individuals with BAs are higher as well.

Hence, it is only fair that students be required to finance their

education. On the other hand, the higher the

share of college graduates in the population, the greater the national ability

to assimilate, utilize and develop new technologies and managerial abilities –

a benefit for the entire society, including those who never stepped foot inside

a university. Therefore, there is

justification for society to participate in funding academic studies (this does

not even take into account the fact that a large part of academia’s cost is the

funding of basic research). But the Israeli scene is unique in

additional realms as well. Part of the

country’s population loses years of market income as a result of mandatory

military service. Furthermore, the older

a person is when beginning academic studies, the greater the personal

obligations and responsibilities, compared with those borne by the much younger

American undergrads. And there is an

additional detail that should be taken into account: Israel subsidizes the

studies of Jews who choose not to serve their country – including those among the

ultra-orthodox who also choose not to work. Consequently, the third option for

solving the tuition issue merges a number of national priorities. It is in our interest to draw closer to the

Israeli narrative two segments of the population that will become a majority in

one generation. It is vital that we stop

discriminating for and against (depending on who, and depending on the issue) ultra-orthodox

and Arab Israelis, and begin providing equal rights alongside the requirement

of equal obligations. Just as the Americans enacted the GI

bill after World War II in order to assist demobilized veterans receive an

academic education, Israel should behave similarly towards those who sacrifice

years of their lives in the service of their country. Every healthy Jew that serves three years of

military service and every Israeli Arab that does three years of national

civilian service – even in his/her own community – or military service, should

be eligible for reduced tuition and for non-interest bearing loans that cover

tuition and subsistence for the duration of the studies. Every healthy individual who does not

serve his/her country should not receive any public support whatsoever for any

sort of studies after the age of 18. These

individuals should pay the full price of universities, yeshivot or any other

institution that they wish to study in. Moreover, it is important to utilize

the fact that Israeli universities are among the best in the world and academic

studies in fields like management, economics, computer science, engineering, medicine

and so on should be opened to foreign students who will pay much higher tuition

than Israelis, but lower in comparison with universities of a similar caliber

abroad. Since it is difficult to

exaggerate the importance of being able to read and express oneself in English in

these fields, Israeli students will graduate more prepared into a globalized

marketplace while many foreigners will return home with a new familiarization

of a young, vibrant and humane Israel that is not usually visible in the

international media. The problem is that even if this third

tuition option is equitable and reasonable, it has no chance of ever passing in

our current system of government. The

inherent structural instability, the incentives for supporting sectoral rather

than national priorities, the systemic inducements that spur cabinet ministers

to work only for themselves and against the prime minister (without relation to

any particular individual who may happen to hold the post at any given time) –

all of these prevent Israeli governments from putting forth and adopting long-term

strategies in many different areas, including some that are existential. comments

to:

danib@post.tau.ac.il

|