|

PDF file

published

in Haaretz on December 13, 2006.

Education Minister in Denial

by Dan Ben-David In a society who’s agenda is

determined by polls, instincts and gut-feelings, there is a continuous search

for “experts” who are willing to provide professional ratification for the

conventional wisdom. Such a world

presents many economists with a problem.

One of the leading, and most original, economists in the world, Steven

Levitt describes this problem well in a unique book, Freakonomics, that

he recently wrote together with the reporter Stephen Dubner: “It is well and

good to opine or theorize about a subject, as humankind is wont to do, but when

moral posturing is replaced by an honest assessment of the data, the result is

often a new, surprising insight.” The problem with conventional wisdom

is not just that it is frequently based on partial information that is often

incorrect, but that conventional wisdom repeatedly becomes the cornerstone for

setting policies. The field of education

in Israel provides one of the more prominent examples of how opinions and

beliefs dominate facts. Education minister Yuli Tamir claims

that the abysmal state of Israel’s educational system is due to three main

problems: too many pupils per class; cuts in the number of instruction hours; and

low teachers’ salaries. The common

denominator that created all three problems, according to Tamir, are the many

budget cuts which are reflected in an expenditure per pupil that is lower than

in most western countries. This leads

the minister to demand a massive budget increase of NIS 7 – but not for

implementing significant changes in the priorities and operating procedures of

her office. After all, the minister

declares on every possible pulpit that she does not believe in reforms. From this set of opinions and beliefs,

upon which Israel’s education policy is based, we move to the facts. The deterioration process in the system was

well underway in the 1990s, while the country’s education budget spiraled up to

levels uncommon in the west. If, as

claimed, the source of the problem is budget scarcity and not the system itself,

then how is it possible to explain what transpired here during those years of

budget increases? Even after the budget cuts of the past

few years, expenditure per pupil – after accounting for differences in

standards of living – in Israel’s secondary education is equal to the OECD (the

organization of developed countries) average.

In primary education, expenditures per pupil in Israel are still 23%

higher than the OECD average. Although the country’s education

budget does not fall below the western average, teachers’ salaries in Israel (here

too, after accounting for differences in standards of living) are only ½ to

⅔ the average OECD salaries. Where

does our education money go? In an

environment that tolerates denial of facts – in this case, regarding the budget

– then there is no need to provide the public with real explanations regarding

problematic policy outcomes. Hours of instruction were also cut. But in spite of this, the total numbers of

teaching hours provided to Israeli pupils aged 7-14 is 13.5% higher than the

OECD average. As the OECD figures

indicate, the number of instruction hours in Israel is greater than in 22 of

the 26 countries. So how is it possible

that in the international tests, the achievement level of Israeli pupils in these

ages scrapes the bottom of the western barrel in core subjects such as

mathematics, science and reading? What

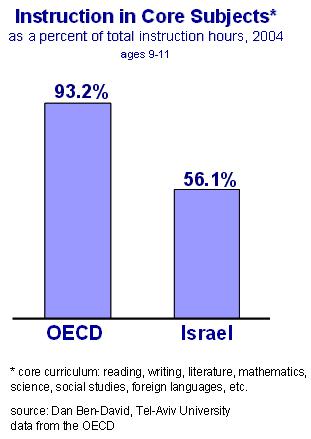

do our schools teach with all these extra hours that we finance? In the case of pupils 9-11 years old, for

example, part of the explanation comes from the fact that OECD countries devote

93% of the instruction time to core subjects, compared to just 56% in Israeli

schools. This is not an issue of

inadequate funds but rather one of inadequate policy. Israeli classes are indeed congested: 27

pupils in primary school classes versus and average of just 21 in the OECD. The lower secondary picture is even worse: there

are 32 pupils per class in Israel while there are only 24 in the OECD. But the problem is not one of a lack of

teachers. The number of pupils per

teacher in Israel is identical to the OECD average: 17 pupils per teacher in

primary schools and 13 in secondary schools.

In other words, the education minister need only ask herself and her

ministry’s workers why Israel’s classes are bursting at the seems, because

neither funds nor teachers nor instruction hours are lacking here. The education system played a major

role – though it was not alone – in causing the serious, steady and dangerous

deterioration of Israeli society. All

the while, this system has been in a state of complete denial. A comprehensive reform will cost considerably

more than current budgets. In light of

the implications of not changing course, it is important that this increase be

funded – provided that the minister demanding the additional resources, at the

expense of other societal needs, internalize the fact that good intentions with

a heavy price tag do not constitute an alternative for true reform in the

thinking and in the operation of the education system. comments

to:

danib@post.tau.ac.il

|