|

PDF file

published

in Haaretz on January 16, 2007.

The High-Risk Roads of Israel

by Dan Ben-David and Avi Naor When it comes to traffic accidents, the

common attitude among drivers as they enter their vehicles is “it won’t happen

to me”. The statistics would appear to

support this belief. After all, the

probability of becoming a casualty on any given trip is close to zero, so who

cannot understand the feeling of complacency that engulfs individuals as they

sit behind the wheel or walk across the street?

The issue of traffic safety barely flickers, if at all, on the personal

radar screens. However, if one takes a step back and

looks at the data from a different perspective, the probability picture darkens

considerably. According to Israel’s

Central Bureau of Statistics, roughly 8,000 people were killed and over 600,000

were injured, more than 50,000 of these severely, on Israel’s roads during the

years 1990-2005 – all this out of an average population of less than 6 million

during this period. If these statistics

will also characterize Israel in the future, then the probability that a person

has of getting injured or killed in a traffic accident during the next decade

and a half is 11%. To illustrate what this implies for a

family of five, the probability that at least one of the family members will

become a casualty – and not just involved – in a traffic accident is 43%. The probability that one of the five family

members will be killed in an accident during the next 16 years is close to one

percent. These are no longer trivial

odds. When one considers the extended

family, then there is hardly a family in Israel that will not suffer a casualty

from traffic accidents during the next decade and a half. These statistics are not part of some

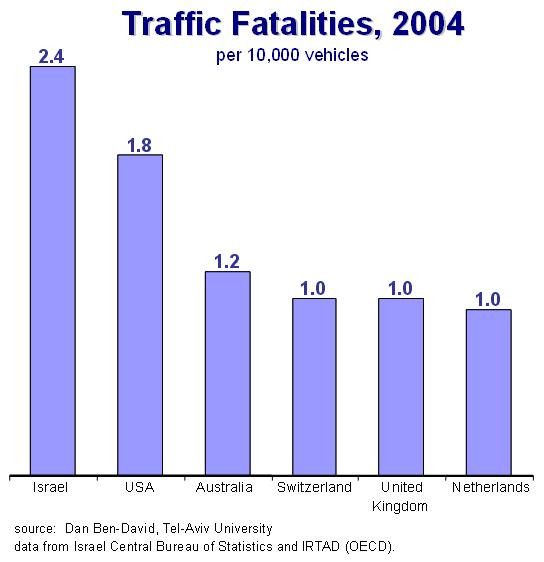

pre-determined fate nor are they representative of many other countries. As is indicated in the graph, the number of

fatalities per 10,000 vehicles in Israel is greater than in the United States

by one-third. It is twice the Australian

level and 2.4 times greater than in the Netherlands and in other countries. What do these numbers mean? Had we lowered the number of traffic

fatalities in 2005 to the level of the Netherlands, the lives of 266 people (60%

of the 448 who died) would have been spared.

Just think how many lives could have been spared over the last decade

and a half. This could have been a

completely different country. How can we lower the number of traffic

fatalities? First, it is possible – and

necessary – to remove many people from the roads by building fast, available

and cheap mass transportation systems. This

is important also from the perspective of improving efficiency in the economy, lowering

production costs and increasing output – with all of the positive implications

that this has on raising living standards and reducing income disparity. When the focus turns to the risk associated

with actual travel on the roads – that is, the number of fatalities per

kilometer-traveled – the situation in Israel continues to look bad in

comparison with other countries: 28% more fatalities than in the U.S., 50% more

than in Australia and Switzerland, 56% more than the Netherlands, and 58% more

than in the U.K. There is considerable

room for improvement. According to one of the leading

researchers in this field, Prof. Ian Johnston, we need to “put five star people

in five star cars on five star roads.”

In other words, traffic safety education is critical, but it is only one

variable in the equation. It is also

important to switch to new vehicles that are designed and built to provide

greater safety. And the third variable, infrastructure, plays a decisive role

in completing the picture. Despite the frequent inclination to

place responsibility for an accident on the “human factor,” the time has come

to redefine what this term actually means.

When narrow road shoulders are constructed, when poles and trees are

placed in close proximity to traffic, when sharp curves are built on intercity

roads, when road markings are inadequate and misleading, when there is no

serious enforcement of laws against the most dangerous traffic violations, then

this is a “human factor” that must be addressed. Hopefully, the new National Traffic Safety

Authority that is now being created will know how to identify and influence the

entire human factor issue in a much more effective manner than we have been

familiar with in the past. Dan Ben-David

teaches economics in the Department of Public Policy in Tel-Aviv University. Avi Naor is the founder and chairman of the

Or Yarok Association. comments

to:

danib@post.tau.ac.il

|