Changing the discourse A visual primer for Israel’s 2019 elections Dan Ben-David Israelis

will soon be heading for the polls.

Knowing how to separate the wheat from the chaff in an environment that

relentlessly bombards us with data is vital.

The visual primer below drills under the often superficial discourse to

provide a vivid picture on Israel’s primary long-term socioeconomic challenges. It is a primer showing where we were in past,

where we are today, and where we are headed – a primer that should interest and

unite all who care deeply about the future of Israel, whether they are

right-wing or left-wing, religious or secular, Jewish or Arab. While

nearly all of the serious election-related attention in Israel tends to focus

on national security issues, that fundamental concept has come to encompass far

more than most are aware of. The past

several years have been relatively good for Israel from an economic perspective,

like an abundant oasis – but one that is currently situated on a very

problematic, and remarkably steady, highway toward the abyss. Contrary to conventional wisdom, ours is not

a predetermined path etched in stone. We

have a say, and a responsibility, in determining the direction that Israel is

headed, but that window won’t remain open forever. The

way we were During

the 1970s, Israel changed its national priorities in some of the more basic

socioeconomic realms – which led to quintessential changes in its primary

long-term socioeconomic trajectories.

The young Israel was poor, inundated by new immigrants with just the

clothes on their backs. It went through

a period of food rationing and wars of existence. But despite Israel’s meager resources, the

founding generation found the wherewithal to build not only towns and roads but

also – for example – hospitals and universities. By

the mid-seventies, hospitals were built from Safed to Eilat, with the number of

hospital beds matching the population’s phenomenal growth rate. By the mid-seventies, seven research

universities had been built and the number of academic researchers in Israel,

per capita, approached American levels. Neglecting

the health system The

number of hospital beds per capita has been in a free fall since the mid-seventies.

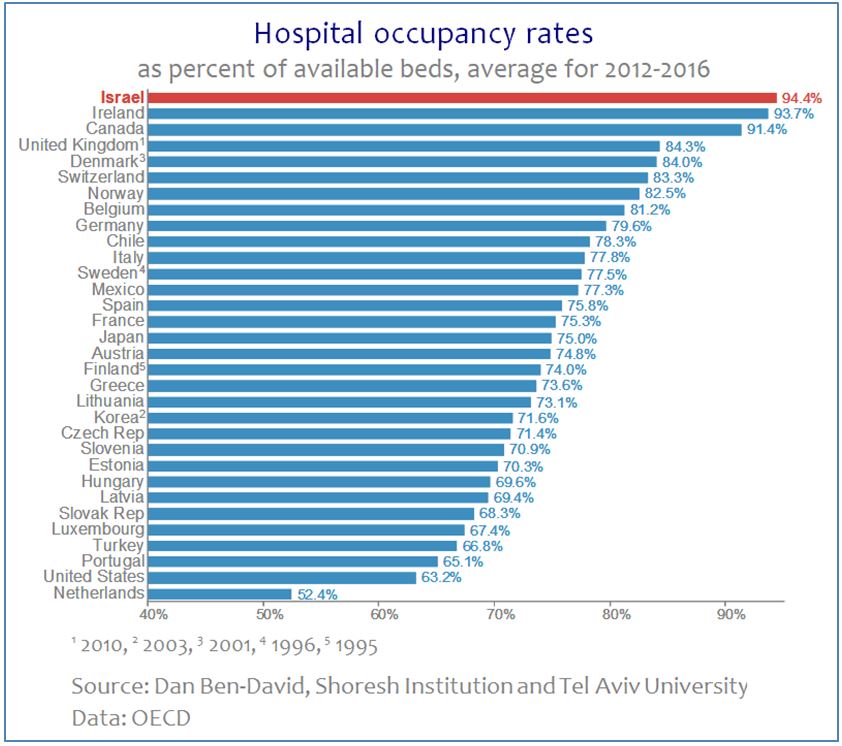

Consequently,

Israeli hospitals today have the highest occupancy rates in the OECD.

The

ongoing neglect of the health system has exacted a price. The dilution of resources and manpower has

not only led to long lines, congestion, suffering and violence by

patients. Over the past two decades, the

share of Israelis dying from infectious and parasitic diseases has doubled.

The

leap in the number of Israeli deaths per capita from infectious and parasitic

diseases places Israel alone at the top of the OECD countries, with 73% more

deaths per capita than the number two country, the United States. The annual number of deaths from infectious

and parasitic diseases is a double-digit multiple of the number of Israelis

killed each year in traffic accidents.

Neglecting

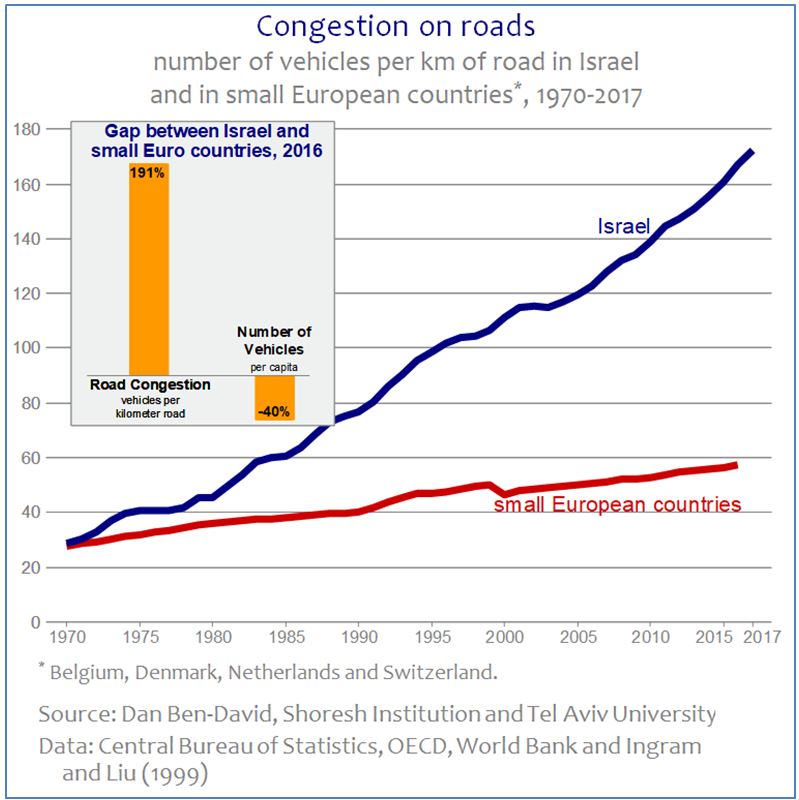

the transportation infrastructure Israel’s

founding generation brought the congestion on the country’s roads to parity

with the average for small European countries in the early 1970s. Since then, Israeli road congestion has risen

to nearly three times the congestion there – and this, despite having 40% less

vehicles per capita in Israel. It is

simply a situation in which there are no adequate substitutes for travel in private

vehicles. The results are extreme

congestion and endless traffic bottlenecks.

Neglecting

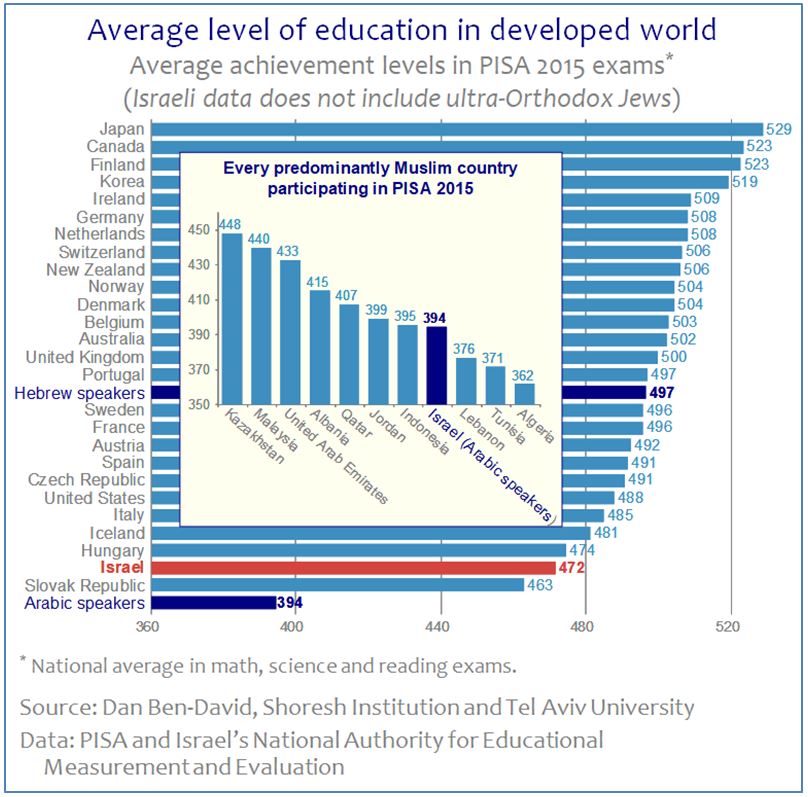

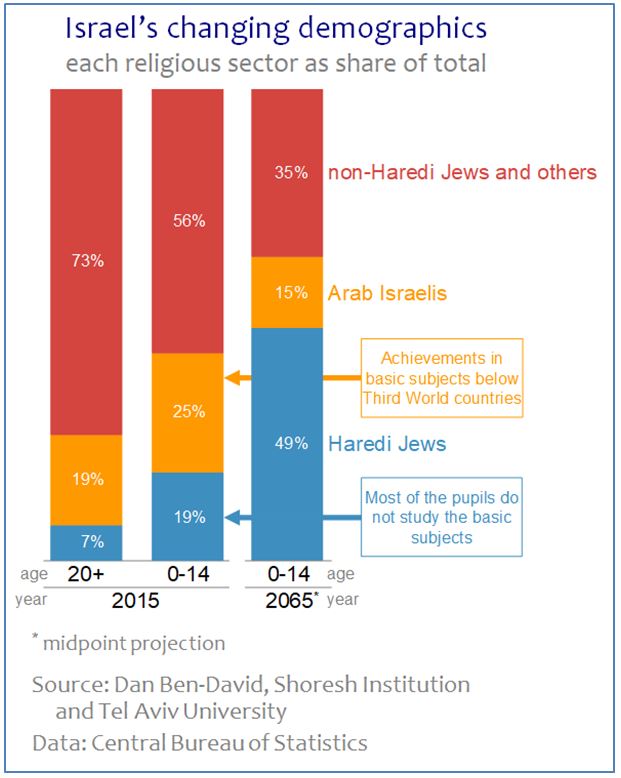

the education system The

achievements of Israeli children in core curriculum subjects are at the bottom

of the developed world – and this is without even taking into account the

ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) pupils, who do not study the core subjects and do not

participate in the international exams.

The achievements of Arab-Israeli children are beneath those of Third

World countries – in fact, below the majority of predominantly Muslim

countries.

The

graph provides a peek at the future since the children from all of the various

countries will have to compete with one another in the global marketplace. This is how the various countries are

preparing their children for that eventuality. Neglecting

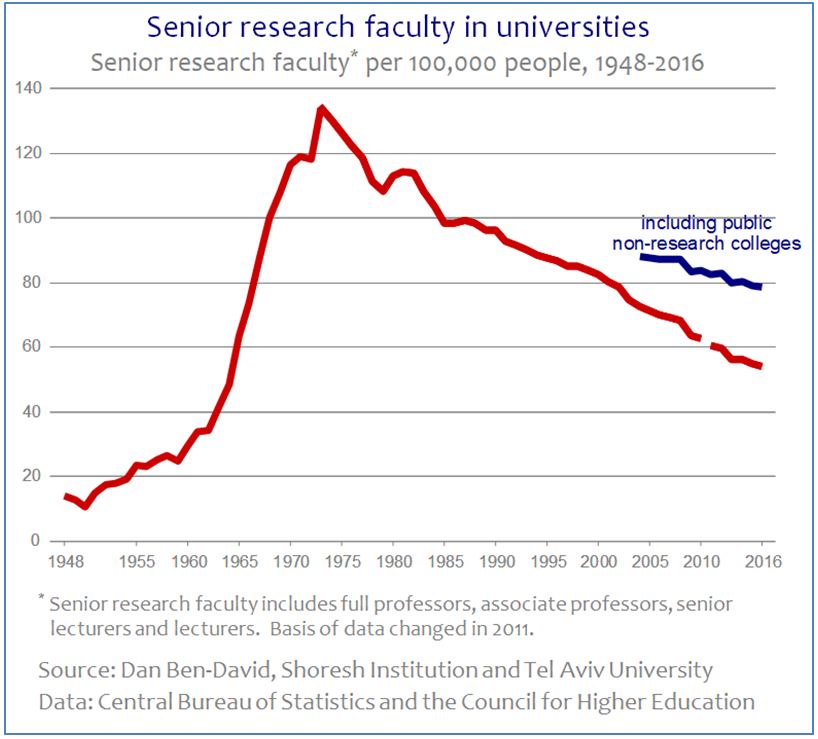

the cutting edge Since

the mid-seventies, Israel’s population has more than doubled. It is considerably wealthier than the

founding generation (GDP per capita has also more than doubled since the

1970s). But the country’s national

priorities changed. Israel has not built

another Technion, or Hebrew University, or another Tel-Aviv University. The number of research university faculty per

capita today is 60% lower than it was in the much poorer Israel of the 1970s.

Results

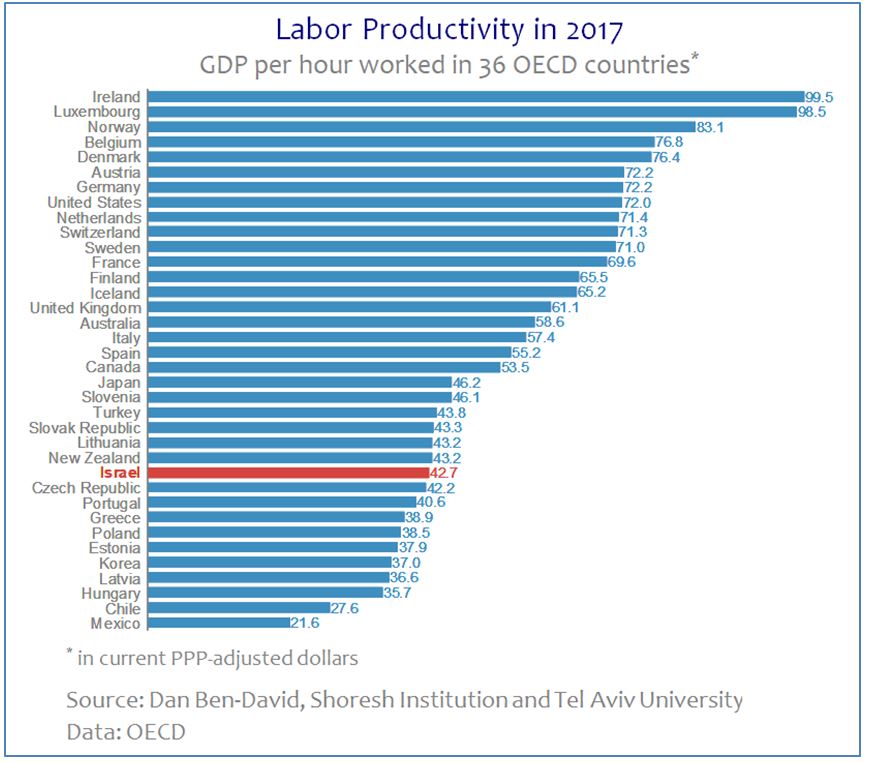

of the neglect With

one of the developed world’s most under-developed transportation

infra-structures and a level of education at the bottom of the developed world,

it should come as no surprise that Israel’s labor productivity is below that of

most developed countries. Labor

productivity is a key determinant of income: if the average amount produced in

an hour by an Israeli is low, then the average hourly wage that the person

receives will also be low.

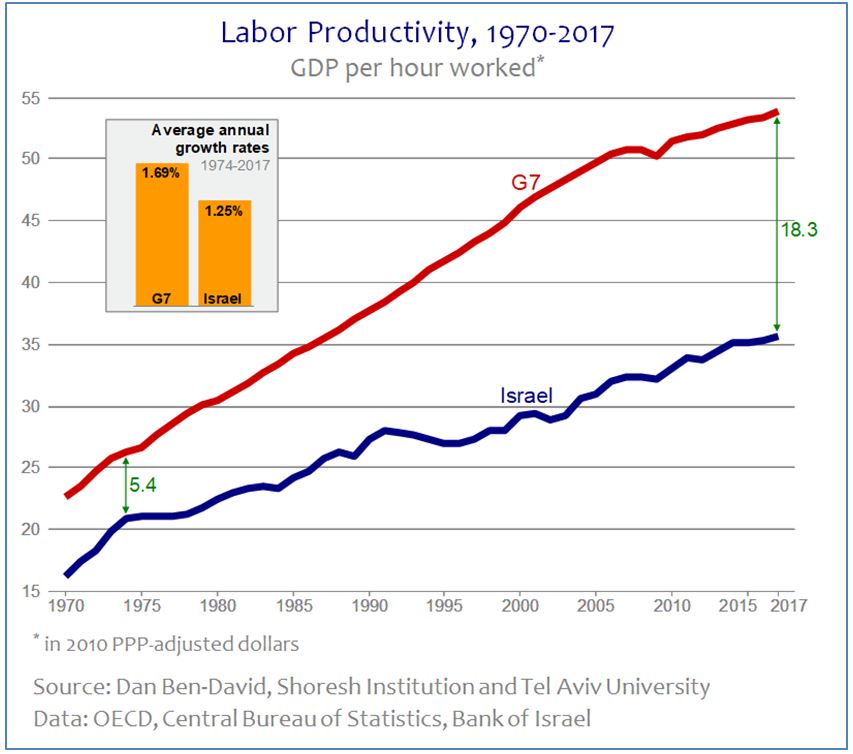

Labor

productivity in Israel is not just low.

It has been falling further and further behind – in relative terms – to

the labor productivity of the world’s leading economies. Since the mid-seventies, the gap between the

G7 countries and Israel has risen more than three-fold. The trajectory of the past four decades will

not be sustainable four decades from today – with all of the implications that

this has on Israel’s future.

The

larger the gap between what educated and skilled Israelis can earn abroad and

what they receive in Israel, the smaller the likelihood that Israeli society

will be able to keep them at home. With

time, it will become increasingly easier – especially for educated and skilled

Israelis – to decide between leaving the country or remaining and earning below

their potential. Such a decision will

become easier still when they’ll take into account that fewer and fewer

shoulders will have to carry a larger and larger burden – from taxes to

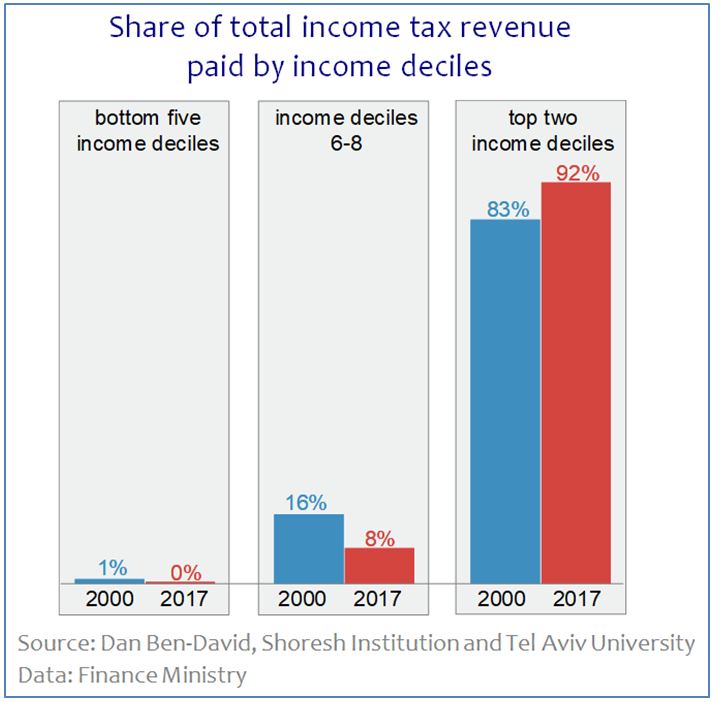

military service. Already

today, the income of half the country’s population is so low that they do not even

reach the bottom rung of the income tax ladder and pay no income tax

whatsoever. 92% of all income tax

revenue comes from just 20% of the population – an increase from 83% in the

year 2000.

If

this is the current situation, what will happen when today’s first graders

reach working age? How many will possess

the tools to work in a modern economy, and how many will need assistance to

survive? When the national leadership

fails to understand or display an interest in root treatment that will require

a change in direction, how many of the young and educated will remain in Israel

to bear a steadily rising tax burden resulting from an increasing number of

needy alongside a decreasing number of tax payers? The

future – if Israel does not wake up in time It’s

time to change the public discourse taking place in Israel and to rethink

outdated paradigms. National security is

not just planes and tanks. It is also

the ability to maintain a First World defensive capability. Roughly

half of Israel’s children today receive a Third World education, and they

belong to the fastest growing parts of the population. A Third World education will lead to a Third

World economy. But a Third World economy

cannot support a First World army – with all of the implications that this has

on Israel’s future ability to survive in the world’s most violent region.

Israel

has reached one of the most decisive crossroads in its history. The national priorities that will be decided

in the coming years, before the country eclipses the demographic-democratic

point of no-return, will determine if Israel will be or will not be in future

generations. |