|

The education system The system’s root problems and socioeconomic

implications by Dan Ben-David When

half of Israel’s children receive a Third World education, they’ll only be able

to maintain a Third World economy as adults.

But a Third World economy won’t be able to sustain a First World army –

a necessary condition for the country’s continued existence in the most violent

region on the planet. Sounds

overly dramatic? After all, this is the

Start-up Nation with some of the world’s best universities and one of its most

educated populations. Among prime

working age adults (ages 35-54), the share of Israelis with an academic degree

is the fourth highest in the world while the number of school years per person

is the third highest. During

an era of shameless expressions such as “truth isn’t truth,” “fake news,” and

“alternative facts,” it would appear that we have entered a phase in which

opinions replace facts and anything goes.

In the 1930s (a particularly exceptional example), a lack of information

helped enable the spread of misinformation.

Today, we are inundated with information – so much data that most people

are incapable of seeing the forest for the trees. This is particularly fertile ground for

persuasive demagogues who make it even more difficult for the general public to

distinguish between the wheat and the chaff.

It’s bad enough when this occurs in other lands. But for a people who get the opportunity for

a home of their own just once every 2,000 years, there are very few degrees of

freedom for us to err and not understand what we see in the mirror. On

the face of it, we appear to have recognized the principle that education is a necessary

condition for a better life – and Israel has done what it does best: opened the

throttle for a full-frontal assault on the target. The share of academic degree holders and the

number of school years per person in Israel today is indeed very high in

comparison with the rest of the world.

But 70 years after attaining independence, with the gates of a new

school year opening, the time has come to finally open up that black box more

commonly referred to as Israel’s education system and blast it with a major

dose of sunshine. It’s possible to be

swept away by unique success stories that do not reflect the bigger picture –

or it’s possible to focus on the core problems and understand what kind of a

country this system is leading us toward. Lots

of education, low labor productivity A

hint at the current state and the direction we’re headed comes from the

economic data. Although Israelis are

more educated – on paper – than the populations of nearly all other

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries, the country’s

labor productivity (i.e. its GDP per hour worked, which in turn determines the

ability to pay higher hourly wages) is beneath most OECD countries. As if this were not enough, Israel’s labor

productivity has been falling further and further behind the G7 average (the

world’s seven leading economies), with the gap between them and us more than

tripling since the 1970s. The

seeming contradiction between Israel’s high rates of education and low labor

productivity can be reconciled by paraphrasing Abraham Lincoln: it’s not the

number of years of your education that count; it’s the education in your

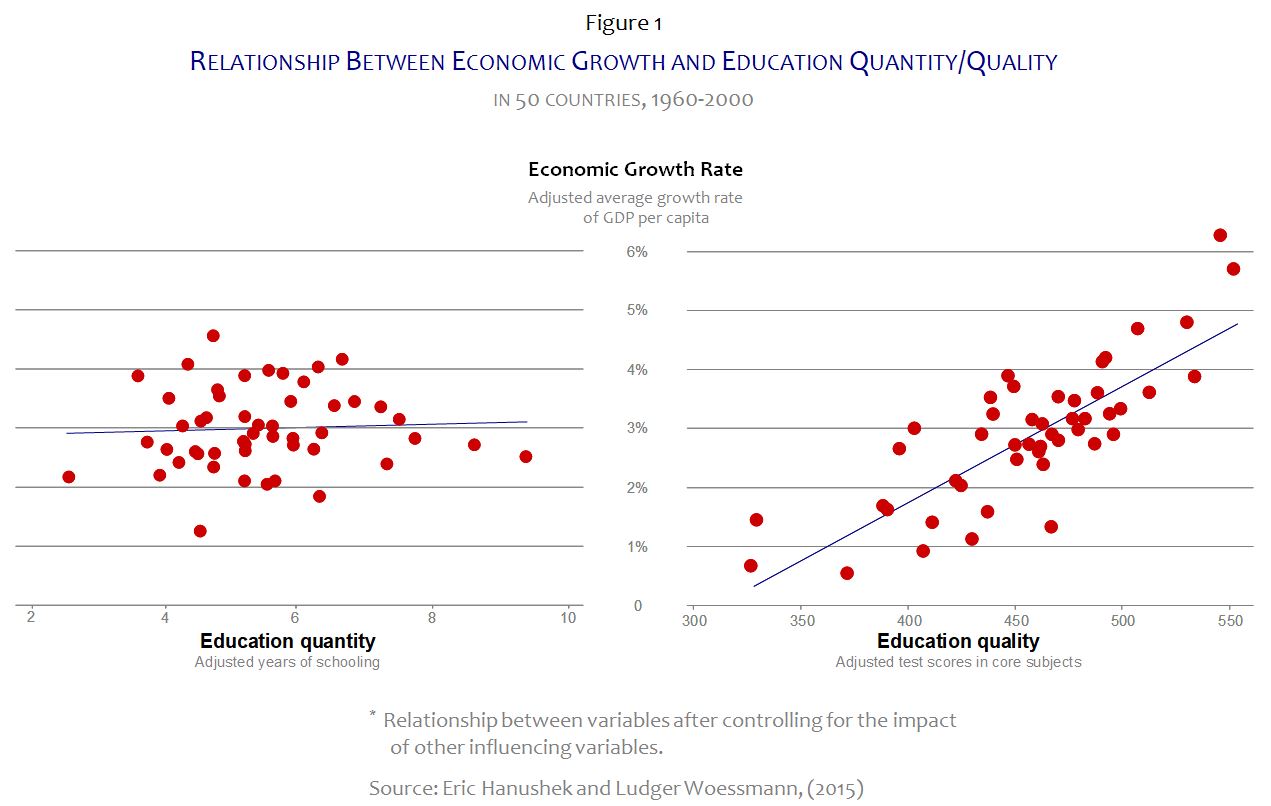

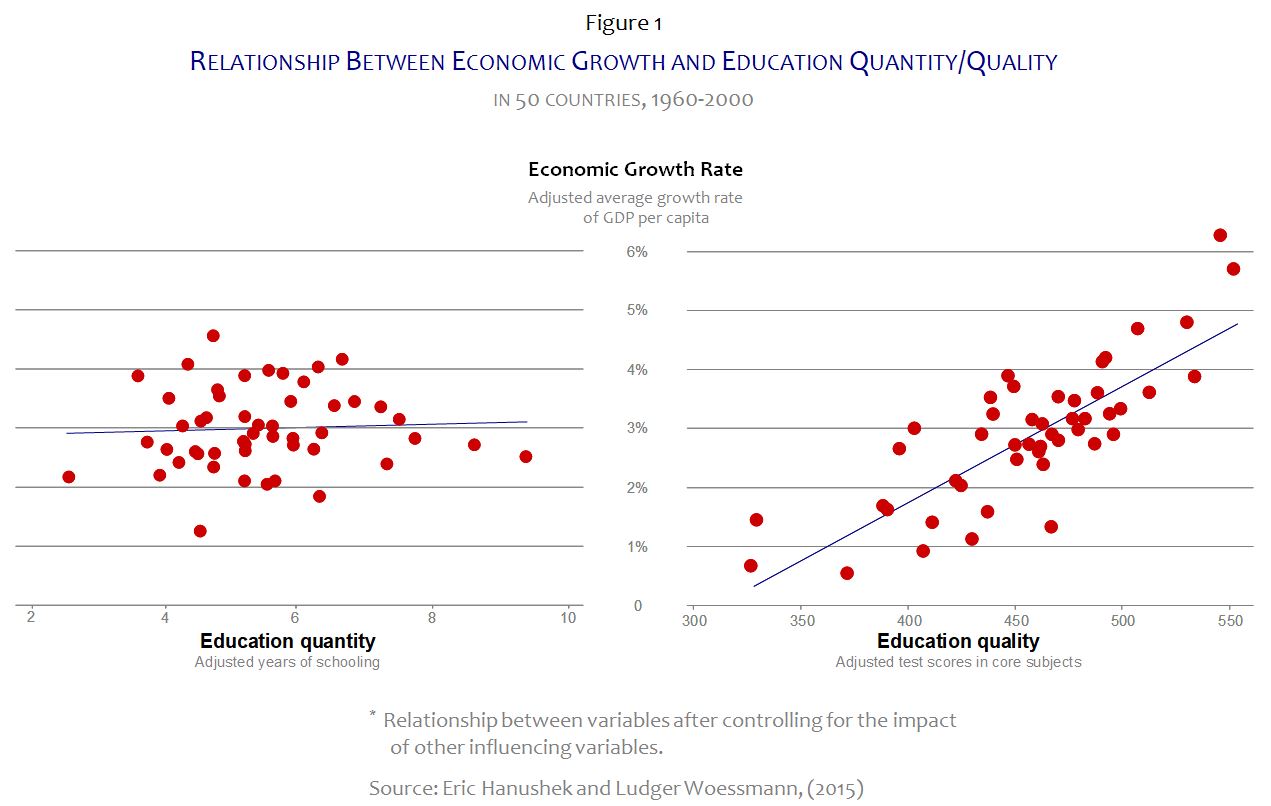

years. The side-by-side comparison in

Figure 1 clearly highlights this, with the left panel displaying the

relationship between the quantity of education and economic growth while the

right panel shows the relationship between the quality of education and economic

growth in 50 countries over 40 years.

There exists a very weak positive relationship between the number of

school years per person (i.e., education quantity) and economic growth

rates. The strong positive relationship,

as evident in the right panel, is with the quality of education – as measured by

achievements in core subjects in the international exams. |

|

|

While

it’s relatively easy to measure education quantity – number of school years,

number of academic degrees, etc. – Israel has failed miserably in measuring and

evaluating the quality of the education that it provides its children. For example, one generation after another of

graduating high schoolers has had to take matriculation exams. But to this day, the education system has

never bothered to calibrate the exams so that it, and we, might be able to know

if the level of knowledge of the country’s children – at least in core subjects

– has risen or fallen over the decades.

Not only is it impossible to compare qualitative changes in Israel over

time, it is also impossible to conduct such comparisons during the same year

across different towns and regions within the country because subjective local

components are an integral part of the grades. The

only national level exam that is standardized over time in Israel is the

Meitzav exam (which focuses core curriculum subjects at the primary and lower

secondary school levels), and even its calibration only began in 2008, 60 years

after the country was born. In general,

achievement levels today are higher than they were a decade ago, a heartening

fact in and of itself – until one sees the share of correct answers out of the

total in the various core subjects.

Education system’s resounding failure As

shown in Figure 2, only 68% of the questions in English were answered correctly

while the results in mathematics (56%) and science and technology (50%)

constitute failing grades for the country as a whole. This is one of Israel’s most resounding

failures – and it doesn’t even take into account the further negative impact on

the national average that would have resulted had the Meitzav exams also tested

the many ultra-Orthodox (or Haredi) pupils who do not study any English or

science.

In

the most recent international Program for International Student Assessment

(PISA) exam, the average score in math, science and reading attained by Israeli

children (once again, without most of the Haredi children, who would have

lowered the national average even further) was below that of every single

developed country in Western Europe, North America and East Asia. When they become adults, these same children

from the various countries will need to compete with one another in the global

marketplace. The

implications emanating from this picture are particularly ominous for Israel,

which, like other small countries, needs to import and export extensively

because of its inability to manufacture all of its needs. As though it were not enough that most of the

Haredi children do not study the material and do not take the exams, the

average achievement level of non-Haredi Jewish children falls below that of

most developed countries. The

achievements of Arab Israelis in the PISA exam paint an even grimmer

picture. Their average score in math,

science and reading is not only below that of the entire developed world, it is

also beneath that of many developing countries.

In fact, the average achievement level of Arab Israelis is below the

average levels in the majority of predominantly Muslim countries that

participated in the PISA 2015 exam (Figure 3).

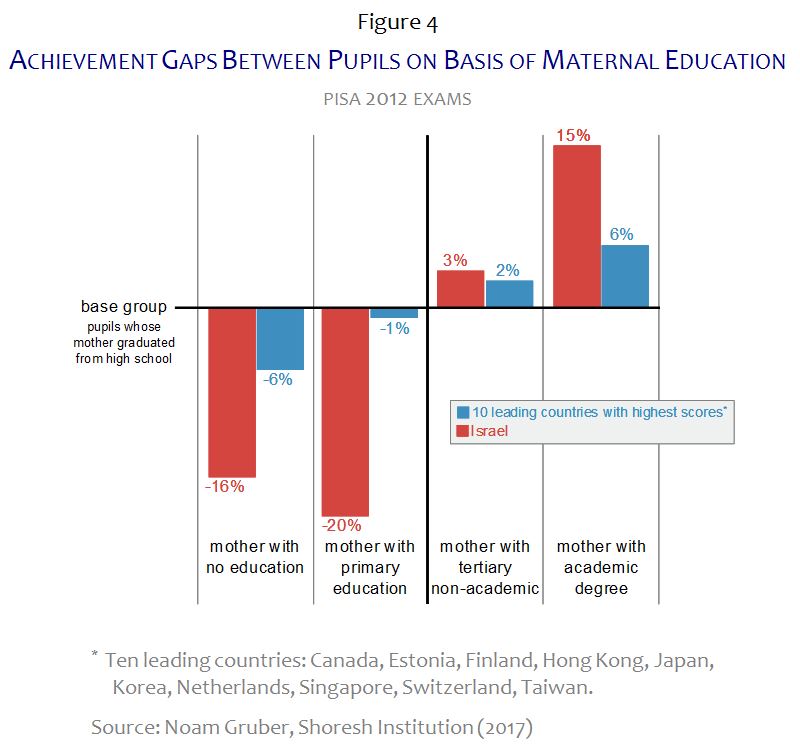

The

primary determinant of children’s achievements is the education level of their

parents – and in particular, the mothers’ education. This is true abroad, and it is true in

Israel. In a Shoresh Institution policy

research paper, Dr. Noam Gruber showed the existence of a strong relationship

between maternal education and their children’s scores. As

indicated in Figure 4, pupils in the ten top-scoring countries whose mother had

no education scored 6% below pupils whose mother graduated from high

school. On the other side of the

spectrum, pupils from those same countries whose mothers had an academic degree

attained scores that were 6% above the scores of pupils whose mothers only

graduated from high school. In Israel,

the link between maternal education and pupils’ scores is several orders of

magnitude higher – reflecting a major indictment of the Israeli education

system’s enormous failure in reducing the gaps that pupils come from home

with. It is no coincidence that

achievement gaps between Israeli children in the core subjects have been the

highest in the developed world in every single exam that has been administered

since the 1990s.

When

roughly a quarter of primary school pupils study in the Arabic language

schools, and another fifth in the Haredi schools, with many additional pupils

studying in religious (non-Haredi) and secular schools situated in Israel’s

social and geographical peripheries, then even though not all of these groups

receive a Third World level of education, it is possible to surmise that

approximately one-half of Israel’s children do indeed receive one – and they belong

to the fastest growing segments of the population. It

is not a coincidence that Israel’s labor productivity is so low, and is

steadily falling further and further behind the G7 countries – not to mention

the country’s rates of poverty and inequality which are among the highest in

the developed world. The outcomes of

Israel’s education system negatively affect us all as the country’s economic

engine is running on fewer and fewer cylinders and finding it increasingly

difficult to pull the entire nation forward.

We need these other cylinders to keep developing and growing as an

economy, not to mention being able to fund the public costs needed for

maintaining defense, education, health, welfare and other infrastructures. Taxing

problem Israel

is more reliant on indirect taxes (such as VAT and sales taxes) than the

majority of developed countries. Such

taxes are considered regressive since their relative burden on income rises as

incomes fall. Thus, as Israel will need

to increase its tax income in the future, it will have to rely more heavily on

direct taxation (primarily income tax).

Already today, though, half of the country’s population pays no income

tax whatsoever since it does not even reach the lowest rung on the income tax

ladder. Some 92% of Israel’s entire

income tax revenues come from just the top two income deciles (average annual

gross income per earner in the ninth decile is about $59,000), and this

percentage has been steadily rising over the years (it was 83% in 2000). If

such large swaths of the population will continue to remain outside of the

country’s primary engine of economic growth, then the resultant price to be

paid will not be restricted only to them.

Increasing budgets will be needed to provide welfare assistance and

services to these individuals, while at the same time continuing to maintain

the country’s remaining infrastructures.

Future governments will have the authority to increase the tax burden to

any heights they deem necessary, but they won’t have the authority to mandate

that all of the young shoulders needed to bear that rising burden must remain

in Israel. Demography isn’t just rates

of fertility and mortality. It is also

the share of educated and skilled individuals who decide to remain or to leave

Israel – which brings us back to the opening sentences of this article. Our

future is in our hands. Not everything

is dependent on education, but unless the education situation in Israel

completely changes direction, all other issues will cease to be relevant. A comprehensive reform of the entire system

is needed. We need to stop confusing

between the marketing of wage bargaining agreements with the teachers’ unions –

as though they were education reforms – and actual reforms that need to focus

on what children study; the way that teachers are chosen, taught and

compensated; and the modes of operation, supervision, measurement and

evaluation of the entire education system.

It is possible that additional budgets may be needed to implement the

reform. But simply throwing more money

at the current system is as effective as throwing money into the sea. Six

days a week Successful

implementation of comprehensive education reform first mandates a recognition

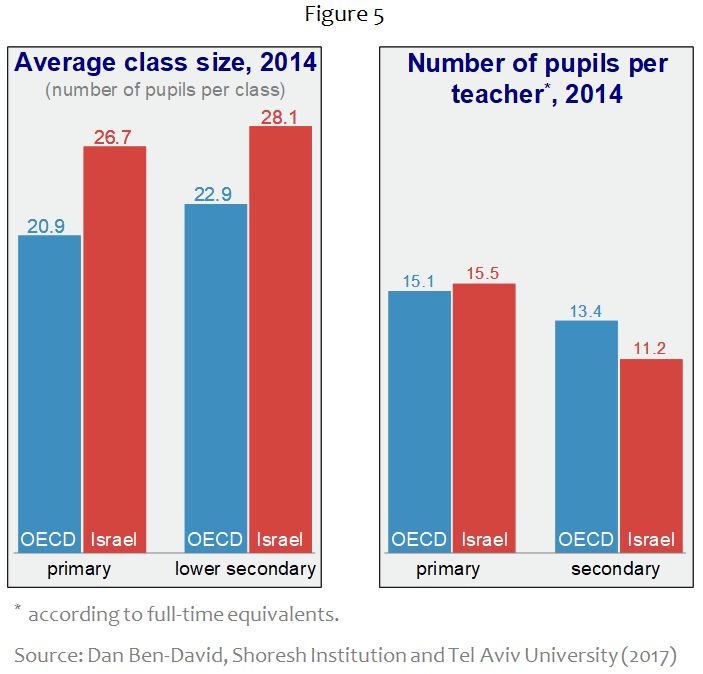

and understanding of the system’s root problems. Crowded classrooms are a frequent

complaint. Whether or not this is indeed

the case, what is more relevant – at least in Israel’s case – is why such

congestion exists in the first place.

While the number of pupils per class is relatively high in Israel, when

compared to the OECD average (Figure 5), the number of pupils per full-time

equivalent teacher in Israel is nearly identical to the OECD average, and is

even slightly below the OECD in lower secondary education. In other words, there is no lack of teachers

in Israel and there is no justification for the extraordinarily large number of

pupils per class.

Lack

of sufficient instruction time is also not the reason for the low quality of

education in Israel. The number of

school days in the country is considerably higher than in all other OECD

countries (in fact, it’s 10% greater than in the number two country,

Japan). As if this were not enough, the

education and finance ministries recently agreed to an additional expenditure

of over $100 million out of scarce budgetary resources in order to further

reduce the number of vacation days – in other words, to raise the number of

school days even further. The

underlying reason why Israeli children have more school-days than any other

developed country is that Israel’s children study six days a week. Not only are five days a week the norm in

other countries, Israeli teachers only work just five days a week, as do most

of the pupils’ parents. It makes no

sense that Israeli children are also not moved to five-day school weeks. As in the case of overcrowded classrooms,

this is not a real problem but rather one of organizational behavior and the

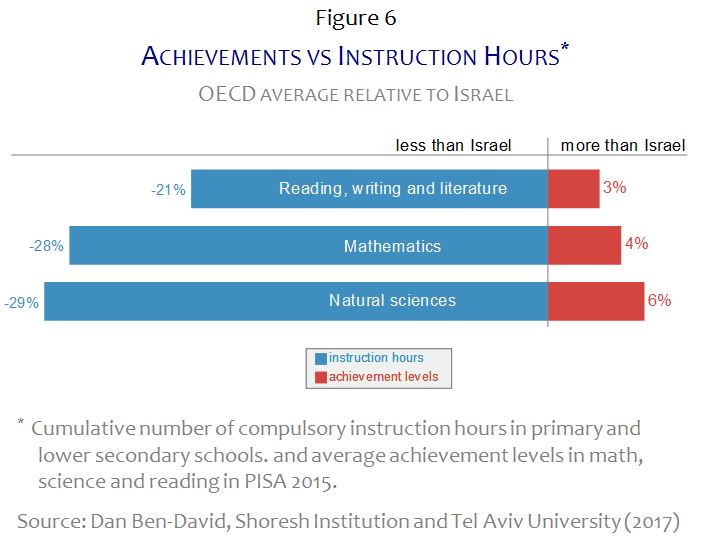

feckless approach that spending more money can substitute for root solutions. Not

only is the low level of Israeli education not due to a lack of school days, it

is also not the result of too few instruction hours, as indicated in Figure

6. The average number of instruction

hours devoted to reading, writing and literature in the OECD is 21% lower than

in Israel, but the average achievement of these same countries in the reading

exam was 3% higher than Israel’s. In

math and science, they study 28% and 29% (respectively) less and attain 4% and

6% (respectively) higher grades.

When

the children of Israel receive so many instruction hours while their scores are

so low, the primary source of the problem is what happens in class during those

hours. There is no lack of possible

explanations – from inadequate lesson plans through discipline problems and

crowded classrooms to the qualitative levels of the teachers. It is also possible that there is an

additional problem, one related to the way instruction hours are measured in

Israel. Do

the country’s pupils really receive so many instruction hours, or is this part

of a setup used to increase salaries?

After all, the education system determines teachers’ pay according to

the number of their instruction hours.

Low salaries are often augmented by converting many activities that are

completely unrelated to frontal class instruction into purported instruction

hours. Thus, instead of directly

compensating teachers for their entire workload, all kinds of machinations are

employed that show up as though actual teaching took place. The greater the extent of this problem, the

larger the degree of distortion in Israel’s education picture, since there is

no way of knowing how many genuine hours of instruction are given to the

children. Education

reform basics And

then there is the question of the teachers themselves, and their professional

levels of competency. There is no doubt

that many teachers are highly qualified and choose the profession out of a

sense of mission and not because of a lack of professional options. But this is not the general defining

characteristic of most teachers. The

distribution pie of first year education students appears in Figure 7. In 2015, some 79 percent of students studied

in teaching colleges with entrance requirements below those of nearly every

academic department in every research university. Consequently, their average psychometric

score (an exam that serves the same screening purpose as the American SAT) was

494, which was below 61% of all those who took the test. An additional 15% of the students studied in

non-research general colleges, with an even lower average psychometric score of

439 – a score that was below 76% of all test takers. Just 6% of the first year education students

studied in research universities. Their

average psychometric grade (617) was higher than that of the two other, much

larger groups, but it was nonetheless below the 617 average that all research

university students attained. When most

of Israel’s teachers are below the general level of the universities, how can

it be expected that they will be able to bring Israeli children to the level

needed for acceptance and success at the universities?

The

concept of education in Israel must change.

The rush to attain academic degrees not worth the paper they are written

on, and the large number of school years at the lowest levels in the developed

world, are no substitutes for actual knowledge.

Education reform needs to be real.

The ministry in charge cannot both administer and supervise the

education system while also holding responsibility for the measurement and

evaluation of its outcomes. The role of

the Education Ministry should be in setting the direction and defining objectives

– including the determination of a higher quality common core curriculum for

all pupils, including the Haredim – and supervising the results. The actual running of the schools, and the

flexibility that needs to accompany this, should be transferred to the school

principals who will be accountable for attaining the goals. Those who are unsuccessful in reaching the

designated targets should be replaced. The

current method for educating teachers in Israel needs to be turned on its

head. Instead of teaching them how to

teach and providing bits of study in various disciplines along the way, future

teachers should undergo the respective screening processes of acceptance to the

various disciplines they are interested in majoring in as undergraduates. After completing their degrees, the graduates

who will have become experts in their fields (at least at the BA/BS level) can

choose if they even want to become teachers, or if they prefer to go in other

directions. If the education system

wants them to teach, it will have to compete with the other alternatives before

them – in terms of wages and also in terms of work conditions. This means providing higher monthly salaries

(after teaching certificates are attained in a considerably abbreviated

process), while demanding longer work hours and shorter vacations, in a manner

consistent with norms that are common in the sectors with which the education

system is competing. As such, it will be

possible to hire fewer teachers who will work more hours and more days, while

being compensated at higher levels. These

are just some of the building blocks upon which a deep and comprehensive reform

of the education system must be based.

What needs to be done is known, and what will happen to the country if

these steps are not taken is also known.

We

are all on the same ship called Israel, and in front of us is an iceberg. It’s possible to jump ship, or it’s possible

to come to our senses and begin changing direction toward a safe harbor. It is in our hands to preserve the sanctuary

that protects us all – Arabs and Jews, Right and Left, religious and secular –

from the alternatives surrounding Israel.

This means that the greater good must begin trumping narrow sectoral

interests. With elections just around

the corner, we urgently need groundbreakers with the vision, courage and

abilities to lead such a change. |