Haaretz, October 10, 2004.

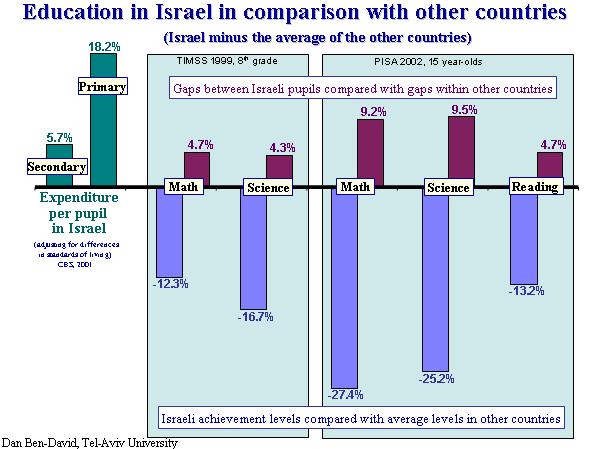

Dan Ben-David Tel-Aviv University Does Israel spend more on education than do other countries? Yes. Is there a need to increase the education budget? Yes. An apparent contradiction, but actually a sign of hope - conditional on the complete adoption and implementation of the Dovrat task force report. A large budget and abysmal results The new Statistical Abstract recently published the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) provides an international perspective on the cost of education in Israel. When the expenditure per pupil in 2001 is adjusted for differences in living standards across countries, it turns out that most of the industrialized countries in the CBS sample spend less on education than does Israel.  In Finland, for example, expenditure per pupil in the secondary school system is just 90% of what Israel spends. The gap is even greater in the primary schools, where Finland spends just 78% of the Israeli expenditure per pupil. In general, educational expenditure per pupil in Israel is 6% higher (in secondary schools) and 18% higher (in primary schools) than the average among the industrialized countries in the CBS sample. The achievements of Israeli pupils bear little relation to the amount that Israel spends on education. The level of achievement by Israeli pupils is 12% to 27% below (depending on the international exam) the average level of achievement in other countries.  As if it weren't enough that the considerable sums of money spent on education in Israel do not contribute to high levels of achievement, they also do not guarantee a reduction in educational gaps within Israeli society. It turns out that while the average level of Israeli achievement is sub par in each of the exams, the gaps between Israeli pupils are 4% to 10% greater (depending on the international exam) than the average gaps within most other countries. Whoever believes that a country must choose between raising the average level of education, or providing more equal education for all, need only look at Israel. Over the span of several decades, we have provided the definitive answer - albeit in reverse - that it is possible to lower the general level of education while simultaneously increasing educational gaps. The severe problems plaguing Israel's educational system are due not only to the quality of its teachers, nor do they stem just from inferior educational programs or from poor management and endemic waste of resources. The lack of flexibility in every part of the system has only amplified and accelerated the decline. The failure is system-wide. In light of the ominous socio-economic consequences emanating from the level education currently provided in Israel, and considering the amount of welfare assistance - and loss of output - that the country will subsequently have to pay in the future, we can no longer continue with business as usual. What to do? In November 2003 the independent ELA commission headed by former air force chief, Herzl Bodinger, completed a two-year study of Israel's educational system and presented its findings to the Education Minister, Limor Livnat, and before the Knesset's education committee. Six months later came the report by the official task force headed by Shlomo Dovrat that was appointed by the Prime Minister and the Education Minister. Two completely separate teams - but two very similar sets of recommendations detailing concrete steps for system-wide changes that will result in an overall reform of Israel's educational system. The system must adopt a much improved - and absolutely mandatory - core curriculum in all of its schools. The entire system of teacher training and certification needs to be completely overhauled, differential budgeting based on need and achievements needs to be implemented, a substantially improved system of performance checks and quality control must be created, and complete transparency of the entire spectrum ranging from all allocation of money to achievement levels and gaps of the pupils (while maintaining, of course, the privacy of individual pupils) has to be introduced. It is difficult to downplay the importance of the Dovrat report. This was a major project undertaken by a group of very serious and talented people who put on the government's table a plan that has the potential of creating real educational improvements - not to mention the rescuing of Israel's public education system - and having a direct impact on the country's dismal long-run (measured in decades, not years) growth, unemployment, poverty and income inequality trajectories. A quote from the ELA report's summation provides some guidance on how the government should deal with the Dovrat task force recommendations. "The transition from the current educational system to the proposed new system will not be cheap. Where will the money come from? Part of it exists in the amounts currently being wasted by the Education Ministry. The remainder will have to come at the expense of other items in the government's budget. Since total public expenditure [i.e. not just on education] in Israel, as a percent of GDP, is greater than total public expenditure in every other western country, there are ample budgetary sources from where the needed amounts may be taken. Even Israel's civilian expenditures - that is, excluding defense spending - exceed the civilian expenditures common in the majority of western countries. The bottom line is that there are sufficient public funds available in Israel to finance the transition period and the necessary changes. This is a clear-cut issue of having to decide where our national priorities lay." It is vital that the Dovrat task force recommendations be immediately and fully implemented by the government and that the required resources be made available in the upcoming budget for 2005. Israel has no budgetary item more important than this.

|