|

PDF file

published

in Haaretz on March 11, 2008.

Canary in the Academic Mine

by Dan Ben-David To a certain degree, the recent

faculty strike and the Shochat Commission report that preceded it exposed a

number of increasingly problematic issues faced by Israel's academic

institutions. But both dealt with only

on the tip of the iceberg. Many years ago, coal miners would

enter the mines carrying a cage with a canary.

In the event of poisonous gas leaks, the canary’s demise provided the

miners with an early warning of imminent danger. In Israeli academia, the brain drain from

Israel’s universities plays the role of the canary. It is important to distinguish between

symptoms – e.g. the brain drain – and the actual problem: the state of Israel’s

universities. The number of European professors in

American universities ranges from one to four percent of all senior academic

staff in the professors’ home countries.

The magnitude of this brain drain has begun to cause considerable

concern in the European Union. But if

Europeans are worried about the migration of their academics to the States, then

Israelis should be nothing less than alarmed.

The number of Israeli scholars in the U.S. represents one-quarter of the

total senior faculty in Israeli academia (including the non-research colleges). The outward migration is distinguished

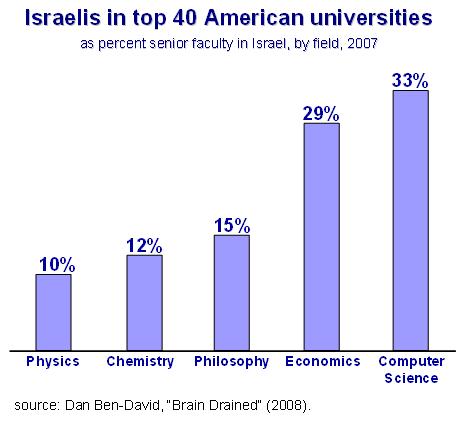

not only by the number of those who leave but also by their quality. As can be seen in the diagram, the proportion

of Israelis in the top 40 American universities is unparalleled. The number of Israeli physicists in just the

leading American departments is one-tenth the entire number of physicists in

Israeli research universities. The share

of top Israeli chemists in America accounts for one-eighth the entire

discipline in Israel. The number of

Israeli philosophers in only the top 40 American departments accounts for 15

percent of the philosophers remaining in Israel. Trans-Atlantic wage differentials

between the United States and Israel are much higher in the field of economics

than in any of the three fields mentioned above. Hence, it is not surprising that the

percentage of emigrating economists in the top American universities alone

equals 29 percent of the total number of economists in Israel’s universities. Salaries differences between the two

countries in computer science are even greater than they are in economics. Consequently, the emigration rate of Israeli

computer scientists is even greater than that of economists, representing a

full third of the entire Israeli senior academic staff in this field. Some leading American departments have no

fewer than five to seven Israelis each. But it is important to emphasize that

the salaries provide only a partial explanation for the brain drain phenomenon. In fact, there are four main reasons for the

departure of many of Israel’s leading researchers from its universities. In addition to (a) the relatively low

salaries – in comparison with employment possibilities abroad and within

Israel’s private sector – there is (b) an insufficient number of faculty

positions, (c) inadequate funding of academic research and laboratories, and (d)

an archaic institutional organization of the universities that is controlled by

the country’s Finance Ministry. This

ministry’s sole preoccupation is to prevent a run on the government’s purse, with

no long-run strategic perspective (this is true regarding its behavior in other,

non-academic, realms as well) and no accountability for any of the long-term

consequences of its policies. Fortunately for us, the country’s

founding generation had the foresight and the wherewithal to make considerable

sacrifices from the little that it had available. They managed to establish a higher education

system that enabled the country’s future graduates to take advantage of the

high-tech revolution when it materialized and to deal with growing security

challenges that we face. The phenomenal

accomplishments of the past few years – Nobel Prizes and cutting-edge

innovations – are the result of past investments. Our children’s ability to survive

economically and militarily in the future will depend on the investments that

we make. It is all an issue of national

priorities. The next articles will

detail how, for three straight decades, Israel has gone and steadily parched

its principal source of national oxygen. comments

to:

danib@post.tau.ac.il

|