Academic Vision and Nightmare

by Dan Ben-David There are four Nobel prizes in the

sciences: Physics, Chemistry, Medicine and Economics. Winning the prize in these fields is

considered the peak of scientific achievement.

There are approximately 200 countries in the United Nations. In only 20 of these are citizens who won a

Nobel prize in the sciences during this past decade. In only four of these countries are there

more Nobel Laureates than in Israel, with five citizens who have won the

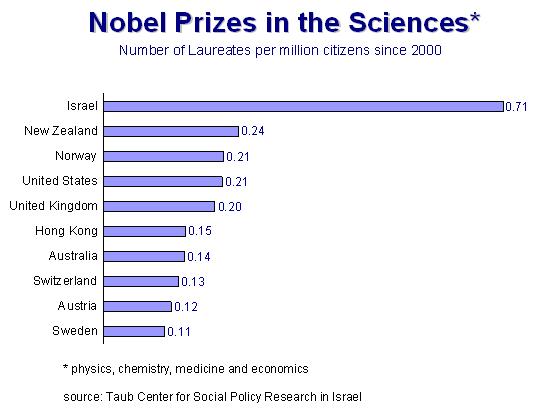

world’s most prestigious science prize. When the comparison is in the number

of Nobel Science Laureates per capita this decade, then Israel is in a league

of its own. The number of Israeli

science Laureates per one million citizens is three times the number in the

countries that follow Israel in the rankings.

Israel’s current Nobel Laureates are

the product of a distant system of higher education – from a past belonging to

a generation with a vision of becoming a light unto nations. In 1950, this was a country with one and a

quarter million people and just 138 senior faculty members. By 1973, two and a half decades after

attaining independence, there were already seven universities with 4,389 senior

faculty members – who represented 134 researchers for every 100,000 persons. This was still a relatively poor

country, with a 1973 GDP per capita of $15,331 (in 2008 prices), but with a

clear vision of future needs. To attain

this vision, that generation was ready to sacrifice considerably in other areas. Their investment prepared the country for the

high-tech onslaught of the 1980s and 1990s.

From the outset, they understood that this country in this neighborhood

would not only need to reach the frontiers of human knowledge, it would have to

move physically them. That insight led

to investments that yielded the Nobel bounties of today. What lies in store for the future? Since 1973, there has been a sharp turnaround

in the public approach to Israel’s research universities. Although standards of living in 2005 were 80%

higher than in 1973, the number of senior faculty per capita fell by

approximately 50% to 71 researchers for every 100,000 individuals. In the Technion, Israel’s MIT, the number of

faculty positions rose during this period by just one researcher – while the

country’s population doubled. In Israel’s

two flagship universities, the Hebrew University and Tel-Aviv University, there

were 14 percent and 21 percent less researchers in 2005 than in 1973. This is no coincidence. Israel’s national priorities underwent a

seismic change. If, in 1978, public

expenditure per student in the universities was 61 percent of GDP per capita, then

by 2005 this expenditure had plunged to a depth of just 29 percent of GDP per

capita – which is about one quarter less than the average among OECD countries. In the capital of the Nobel Prizes in

economics, the University of Chicago, it is common to state that there are no

free lunches. Israel’s founding fathers

knew this, and the meal that they prepared is the one that we are receiving

nourishment from today. But what will

become of the next generation – the one that for years has been receiving the

worst education in the western world even before reaching the universities? Who will make the inventions that will

compete with the industrialized world and with the awakening giants? Who will invent the military advantages that

compensate for Israel’s numerical inferiority against those wishing to destroy

it? Who will be the researchers who will

teach the teachers, the engineers and the scientists who will lead the next

generation? Roughly half of the academic senior

faculty in Israel is over the age of 55.

The country’s labor laws mandate that they go home within one decade. Who will replace them? Once, there was a poor country with a

gigantic vision. It exceeded all

expectations. Those were the days.

|