|

PDF file

published as two separate articles

in Haaretz’s 60th Independence Day edition on Israel’s successes and failures, May 7, 2008.

Israel’s Academia – The Bright and Dark Sides

by Dan Ben-David First

Article The

Bright Side of Israel’s Academia The story of higher education in

Israel is a story about one of the jewels in the crown of the Zionist movement. Annual Israeli incomes averaged just $6,000

during the 1950s and $10,000 during the 1960s (according to GDP per capita in 2005

prices) – about half of American incomes at the time and roughly a fifth and a

third, respectively, of Israel’s current living standards. Despite its meager resources and the

relentless attacks on its physical existence, the Israel’s combination of

vision, determination and tremendous sacrifices provided the country with seven

state-of-the-art research universities within two and a half decades of its

birth. How good did these institutions become? In the field of economics, for example, European

countries were ranked according to the average number of published pages per

faculty member in the top eight economics research journals over a span of

three decades, from 1971 through 2000. In

the accompanying table, England – with its London School of Economics, Oxford

and Cambridge Universities – serves as the base country. Below it are Sweden, the country that bestows

Nobel Prizes, with just half the number of published pages as the English, the

Netherlands, with less than a third, Italy, with less than a quarter, and Finland

– with a primary and secondary school system that is the envy of the western

world – with a research yield that is less than a fifth of the English. In first place, above the English, were

Israel’s economists. For three decades, which

began just over two decades after the country’s birth, Israeli economists

published not 10% more and not 20% more, but seven times the English research

output in the top academic journals. In general, when moving from one field

to another over the past decade, from chemistry and physics through economics

and computer science, there are two, three and sometimes up to five Israeli

universities consistently ranked among the top 150 in the world in each of the

fields (on the basis of citations in scientific journals). The country’s academic excellence is evident

not only in the recent Nobel Prizes that its scholars received, but also in the

exceptional number of Israelis that have been invited to study and to teach on

a permanent basis at leading universities around the world. First-class research universities have

an important role to play in every country.

This is particularly true when the economy in question has a labor force

no larger than a single western metropolitan area – and is situated on a

sandbar in the middle of a very turbulent ocean. This perspective makes it possible to

understand the magnitude of the miracle that occurred here. Israel’s universities nourished the

environment that enabled the invention and development of unique products and

processes that allowed us to survive – and even prosper in some fields – in the

merciless competition of the global economy, and enabled Israel to break

through the frontiers of human knowledge time and again to continuously upgrade

and fortify the defensive shield that assures our existence against all threats

and against all odds. Second

Article The

Dark Side of Israel’s Academia First-class universities are first and

foremost the professional homes of leading researchers and scientists, individuals

who bring honor – not to mention scientific, economic and cultural value added

– also to institutions that are not Israeli.

Therefore, what can one expect when high personal caliber is merged with

a domestic managerial setting devoid of the tools necessary for dealing with

foreign talent-poaching of Israelis? The actual picture is grimmer still

since not only are foreigners hunting for young Israeli talent, but we are also

giving that talent the boot with our own feet.

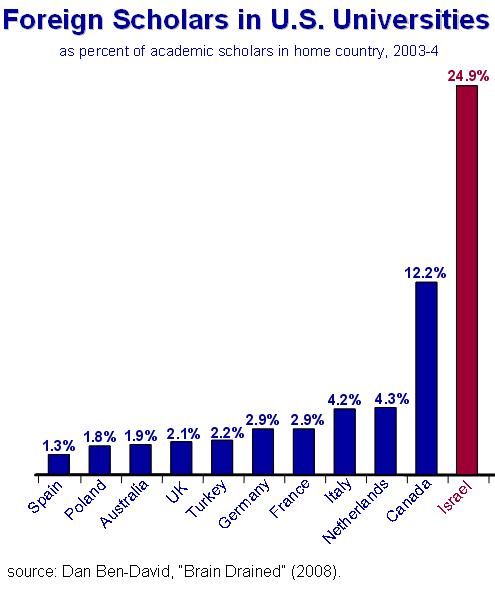

As indicated in the diagram, we have reached a situation in which the

number of Israeli scholars in the U.S. represents one-fourth (!!) of the entire

senior faculty remaining in Israeli’s universities and colleges. It is no coincidence that the share of senior

Israeli faculty in the States is six times the share of academic emigrants from

the leading European country. It is also

no coincidence that the share of Israeli scholars holding full-time positions

in the top 40 American departments in fields like chemistry, physics, philosophy,

economics and computer science is unparalleled. Academic salaries in Israel have

consistently declined in relation with academic salaries abroad and in relation

with salaries in relevant private sectors within Israel. Therefore, why should it be surprising that a

large number of our most gifted individuals are looking for the door – or are

choosing not to even enter academic life altogether? As if salary gaps were not enough, we are

also witnessing increasing gaps in the funding of basic research between Israel

and other countries – which in turn not only harms domestic research but also

impairs the possibilities for personal promotions in the future. Another domestic boot in the pants

comes from a steady decline of roughly 50%

in the per capita number of positions in research universities. An entire generation was abandoned on the

outside, even those wishing to return despite the large gaps in salaries and

research funds. External micromanagement

that is blind to long-run considerations has imposed destructive constraints on

the universities that are reflected in (among other things) non-provision of

regular full-time positions for new graduates, forcing them to work as external

teachers with disgraceful wages, scandalous social benefits and non-existent

research conditions – which then guarantee that these individuals will be

pushed farther and farther behind the research frontier, and their academic

fate will be sealed. Israeli universities – which enabled

the country to reap the benefits of the high tech revolution when it erupted, and

made it possible for us to maintain an existential qualitative advantage in the

realms of industry and defense – are products of the investments made by our

founding fathers’ generation. But the

much wealthier subsequent generation diametrically changed Israel’s national

priorities and reallocated its resources, transplanting the national

perspective with sectoral and personal ones, replacing strategic planning with

blind faith, swapping common sense with obsolete ideologies – and supplanting

the great hopes that our generation was raised on with the black hole that we

may bequeath to our children’s generation, if we don’t get our act together in

time. comments

to:

danib@post.tau.ac.il

|